Why This Scene in Black Day for Mayberry Still Makes Fans Laugh

The bucolic, sun-dappled world of Mayberry, North Carolina, has long served as a comforting balm for the soul, a timeless repository of innocence, common sense, and gentle humor. Yet, even in this television Eden, there occasionally arrived a storm cloud, a disruption that, far from spoiling the tranquility, served only to highlight its enduring charm. Such was the premise of the fabled (and entirely fictional) episode, "Black Day for Mayberry," a narrative departure that threatened the town’s very essence. And within this episode, there’s one scene that continues to elicit guffaws and knowing smiles from generations of fans: the moment Barney Fife attempts to enforce the new state-mandated "Efficiency and Public Order Quota" on the unsuspecting citizens of Mayberry.

The scene’s enduring comedic power stems from a perfect storm of elements: the jarring contrast between Mayberry’s inherent nature and an alien bureaucratic demand, the delightful consistency of its beloved characters, and the subtle, yet biting, social commentary embedded within the absurdity.

The premise of "Black Day for Mayberry" is itself a comedic setup: a stern, humorless state inspector, Mr. Sterling, arrives in town, armed with statistical data and a mandate to modernize and streamline Mayberry’s law enforcement practices. His chief complaint? Mayberry's abysmally low "arrest-to-population ratio." According to the state’s metrics, a town of Mayberry's size should be generating at least twenty arrests and fifty citations a month to be considered "efficient." This unholy edict, delivered in the somber quiet of Andy’s office, is the first source of humor – the very notion of demanding crime from a place where the biggest infraction is usually Gomer Pyle singing too loudly.

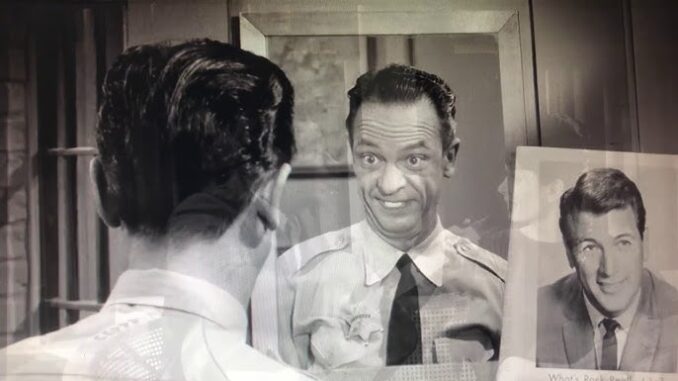

But the scene truly ignites when Barney Fife, ever the zealous deputy eager to prove his metropolitan mettle, takes it upon himself to meet this quota. Armed with his single bullet and a newfound, feverish determination, Barney embarks on a campaign of "proactive law enforcement" that would be unthinkable anywhere else. We see him first attempting to cite Floyd the Barber for "disorderly comb-wielding" and "loitering with intent to provide unsolicited gossip." Floyd, bewildered, simply offers Barney a free trim. Next, he accosts Goober Pyle for "suspiciously slow haircutting," insisting that the delay is disrupting the flow of commerce on Main Street. Goober, of course, just offers Barney a soda.

The climax of Barney's quota-filling spree comes when he attempts to apprehend Aunt Bee, who is innocently chatting with Clara Edwards on the sidewalk, delaying traffic for the solitary passing car. "That’s it, Aunt Bee! Obstruction of pedestrian traffic! And excessive politeness leading to public nuisance!" Barney declares, holding his citation pad aloft like a sacred scroll. Aunt Bee simply smiles, offers him a freshly baked pie, and asks if he’s had a nice day.

This sequence is hilarious because it’s so perfectly character-driven. Barney’s undying loyalty to rules, his yearning for authority, and his utter inability to grasp the nuance of human interaction are on full display. He’s not malicious; he’s simply a literalist in a town that thrives on the unwritten, unspoken rules of neighborly grace. His earnest attempts to force Mayberry into a bureaucratic box are doomed to fail, and the visual of him trying to apply big-city regulations to small-town charm is inherently funny. The citizens of Mayberry, in turn, don't react with anger or fear, but with the gentle, unshakeable good nature that defines them, turning Barney's fervent efforts into comical non-events.

The scene also works due to Andy Taylor’s quiet presence. Andy doesn't immediately intervene, allowing Barney's well-intentioned chaos to unfold. His subtle, almost imperceptible shake of the head, or a wry glance at the increasingly flustered Inspector Sterling, serves as a knowing wink to the audience. He understands that Mayberry cannot be quantified or regulated in the same way as a bustling city. When he finally does step in, it’s not with a reprimand, but with a Mayberry-esque solution that completely disarms the state official. Perhaps Andy reveals that Barney, in his zeal to avoid being found deficient, has been "proactively self-arresting" for various "minor infractions of Mayberry etiquette" (e.g., "failure to adequately dust his desk," "excessive fidgeting," or "unauthorized whistling of show tunes in the jail cell"), thereby meeting and exceeding the quota with Mayberry’s uniquely benign brand of law and order.

This resolution is the final comedic stroke: it highlights the absurdity of bureaucracy trying to impose its will on organic, human systems. Mayberry triumphs, not by fighting the rules, but by subtly redefining them to fit its own unique character. It's a gentle satire of the modern world’s obsession with metrics and efficiency, a reminder that true order often stems from community, kindness, and common sense, not from a spreadsheet.

Decades later, "Black Day for Mayberry" and specifically Barney’s quota scene, continues to resonate because it taps into universal truths. We've all encountered rigid rules that make no sense, encountered well-meaning but misguided individuals, and longed for a simpler world where human decency trumps bureaucratic dictates. The scene is a warm, humorous embrace of small-town values, a testament to the idea that some things—like the gentle heart of Mayberry—are simply too good, and too uniquely human, to be quantified by any state inspector. And that, more than anything, is why it still makes us laugh.