The man who revolutionized TV and redefined our national sense of humor opened up to Esquire in 1981.

Thirty years ago Norman Lear, twenty-eight, was flying the redeye from New York, descending into LAX. At the window beside him sat Ed Simmons, looking down at the lights. Two years earlier Lear and Simmons had been hustling furniture and baby pictures down there, door to door, but now they had written the first Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis show together, and it had aired the night before, and it had been big: “Everyone was talking,” Lear remembers with a showman’s reflexive hyperbole.

Simmons watched the lights of Los Angeles wink back at him, and he wondered out loud: “How many of those people did we make laugh last night?”

Thirty years later, jetting east to attend a testimonial dinner for Walter Cronkite at the Waldorf-Astoria, the fifty-eight-year-old Lear looked down through the clear night at the heart of the country: “There were all those twinkling lights, all those houses, the people in them. And it came to me that it was almost possible—not really probable, I know—it was within the reach of my imagination that I had at least once made every person in America laugh.”

Well, that’s something. Taking account of Lear’s success—partnership in a company that did more than a quarter billion in sales last year, all those Emmys, the enshrinement of Archie Bunker’s chair in the Smithsonian Institution, street recognition—to make a whole country laugh is something to do.

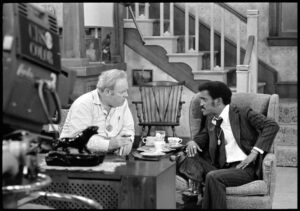

By the mid-Seventies more than half the population of this country, inclusive of newborn babes—120 million people—watched one or another of Norman Lear’s weekly comedies. He has been said to have earned “a power and influence perhaps never attained by anyone in the history of entertainment.” Well before Archie received a vote at the 1972 Democratic Convention, pundits were writing about a “Bunker vote” reflecting the lower-middle-class anger at a tight economy and loose permissiveness. Richard Nixon watched All in the Family and thought it was rotten that Lear let Archie Bunker’s football-playing school friend be revealed as homosexual: “That was awful,” said the President of the United States. “It made a fool out of a good man.”

Money poured in, an irresistible tide. By 1972 revenues from shows produced by Lear and his partner, Bud Yorkin, were reported at about $5 million. By 1979, the year after Lear quit his active participation in the shows he had spun off and conceived, the syndication library was said to be worth $100 million, maybe twice that. Sally Struthers had posed for Gloria Stivic paper dolls; an LP of Archie’s lucubrations had hit the top-100 chart in Cashbox magazine; there were T-shirts and beer mugs.

During the past ten years Lear has been courted by Presidents and would-be Presidents, for his good sense as well as for his influence and money. He has opinions, deplores many things, signs petitions. He keeps company with meritocrats, that loose association of people who have done something and who recognize one another. Sociologists fabricate theories based on his fabrications. He has put a recent President of the United States on hold. Not bad for a door-to-door salesman, son of a door-to-door salesman.

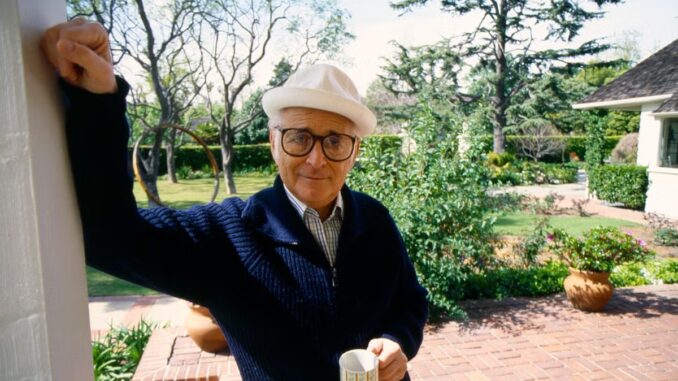

Lear is small for such a visible fellow, compact and fastidious. He has the drooping eyelids and lips, the knowing dolor common to first-rate comedians. Most of the time he wears a kind of costume; its signature is a canvas porkpie, his lucky hat, worn with its brim up in the style of the Dead End Kids. The rest is tailored slacks and a blue Breton sweater with white buttons at the shoulder. His second wife, Frances Loeb, gave him a fisherman’s hat like this twenty years ago (four years after they were married) to discourage him from nervously picking hairs from his head while he wrote and rewrote gags and skits, usually on or past deadline, a three-ulcer way to make a living. Despite his hat and the luck it may have brought him, he’s bald on top, with a close-cut white fringe at his temples.

In conversation his manner is serene and exact but not cool. Even by the casual standards of southern California, where a perfect stranger will call you “Baby” (or, more precisely, “Hey, Baby!”) over the telephone, Lear’s declarations of affection come quickly and forcefully. During the worst of his serial censorship battles with CBS he hugged one of his biggest opponents, the network’s president: “It’s easy for me,” he explained, “to throw my arms around [Robert Wood] and say ‘Hi’ at the beginning of any meeting.” Familiarity and quick kinship are his purpose and his temperamental mark; he’d hug a lamppost if he couldn’t find anything else to hug. At worst, this has nurtured a weakness: “I want people to like me. And I go too far to make them like me.” Still, network executives have had a difficult time liking Norman Lear. In 1971 he needed CBS more than it needed him, despite some success as a comedy writer for television. He had written and produced and directed movies too, most of them modestly ambitious and modestly received. He was not Big or Expensive.

During the late Sixties he had bought American rights to a BBC series, Till Death Us Do Part, about a hate-crippled cockney, Alf Garnett. ABC financed a couple of pilots of Lear’s version (Those Were the Days), starring Carroll O’Connor and Jean Stapleton as Archie and Edith Bunker, and then dropped the project. It stayed dropped for two years, till 1970, when CBS poked at it with a long stick and, trembling a little, picked it up. The network might have hoped for Lear’s gratitude and pliability. The network was soon disappointed.

Lear has chosen, in the collaborative circumstances of the entertainment business, to give himself the power and responsibility of choice, to run his own store and his own risks. While he deserves credit for guts and has been given credit—awards and testimonials and great riches and the respect of his colleagues—he has also been a pain in the ass for CBS. In 1975 the FCC and the networks cooked up something soon called the Family Hour.