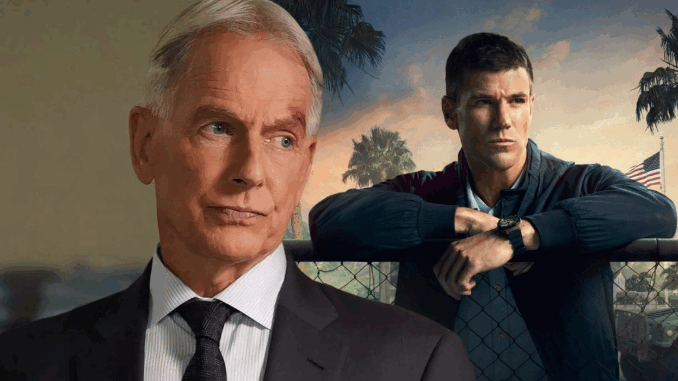

The NCIS Franchise is one of television’s great success stories. With the flagship series spanning over two decades and multiple successful (and less successful) spin-offs like NCIS: Los Angeles, NCIS: New Orleans, NCIS: Hawai’i, and the highly anticipated NCIS: Tony & Ziva, the naval crime procedural has proven itself a sturdy, relentless television machine. Yet, a recent misstep in the newest spin-off has brought a glaring, long-standing issue within the franchise’s storytelling into sharp focus.

The issue? The violation of a literary principle that is a cornerstone of dramatic fiction, a concept articulated 136 years ago: Chekhov’s Gun. The blatant disregard for this fundamental rule highlights a larger, worrying trend of lazy writing that prioritizes formula and simplicity over compelling, structured narrative.

The Misfired Principle: What is Chekhov’s Gun?

The principle is attributed to the legendary Russian playwright Anton Chekhov, who famously advised:

“One must never place a loaded rifle on the stage if it isn’t going to go off. It’s wrong to make promises you don’t mean to keep.”

In modern literary terms, Chekhov’s Gun is the concept of setup and payoff. Every element introduced into a story—a unique object, a specific piece of dialogue, or an unusual character quirk—must have a narrative purpose later on. If a plot device is introduced, the audience expects it to matter. Failing to fire the gun is not merely a missed opportunity; it’s a broken promise to the viewer, leading to a sense of pointlessness and narrative clutter.

The Recent Violation

The violation occurred in the new spin-off, NCIS: Tony & Ziva. The series, which follows the fan-favorite former agents on the run across Europe, is expected to deliver high-stakes spy drama. However, in a recent episode, the show committed the cardinal sin of introducing a specific, crucial object—a loaded weapon hidden for protection—only to have it inexplicably vanish from the storyline without ever being used. The narrative purpose of this weapon, a classic example of a “gun on the wall,” was entirely nullified.

While it’s important to note that Chekhov himself occasionally broke his own rule, doing so successfully requires a deliberate, thematic choice. In this case, the disappearance felt like a simple lapse in continuity, a piece of set dressing that the writers forgot to incorporate into the action. It exposed a weakness in plot structure that has been growing across the entire franchise for years.

The Larger Problem: Telling, Not Showing

The misfire of Chekhov’s Gun in the spin-off is not an isolated incident; it is a symptom of a larger, systemic problem in the NCIS franchise’s writing: a reliance on “telling” the audience information rather than “showing” it through action and procedure.

1. The Magical Forensics Lab

The most frequent criticism of the procedural genre, and NCIS in particular, centers on the forensics lab. The principle of Show, Don’t Tell dictates that the audience should be shown the investigative process. On NCIS, however, the lab often functions as a plot accelerator. A complex piece of evidence that would take weeks to process in the real world is solved in a matter of minutes by a charismatic technician who simply tells the team the answer.

Instead of showing the meticulous, painstaking process of linking evidence—the “gun” of the investigation—the writers simply “fire” the solution via expositional dialogue. This cuts corners, speeds up the pacing, but robs the audience of the satisfaction of a truly earned breakthrough.

2. Character Development via Dialogue

The classic NCIS characters—Gibbs, DiNozzo, Ziva, and later replacements—have always been defined by a shorthand. Gibbs’ “rules,” Ducky’s meandering anecdotes, and Tony’s film quotes were established character tics. But in recent seasons, the emotional weight of characters has often been relayed to the audience through dialogue, not action.

A new agent’s “dark past” is often stated by another character or the character themselves in a brief, emotional moment, rather than being shown through sustained, impactful behavior or a dedicated storyline. The franchise’s longevity has seemingly led to a comfort with character serialization over character evolution, where traits are recycled rather than developed.

3. The Lack of Internal Stakes

When Chekhov’s Gun is ignored, the stakes are diminished. If an object is introduced as a threat or a crucial element and then dismissed, the audience learns that the dramatic tension is manufactured.

Across the franchise, this manifests in the constant use of “off-the-books” operations and “personal connection” cases, where the danger is constantly escalated but rarely results in lasting consequence. Characters are repeatedly shot, kidnapped, or subjected to trauma, only to be entirely fine by the next episode. The figurative “guns” of personal danger are fired weekly, but their impact is immediately reset, creating a kind of emotional fatigue for long-time viewers.

The Streaming Era’s Influence on Procedural Writing

The problem of violating writing principles is compounded by the realities of the modern television landscape. As the NCIS franchise expands into the streaming world with exclusive spin-offs, the pressure to maintain a high volume of comforting, easily digestible content increases.

The procedural format is designed to be a “steady ride”—predictable in structure and comforting in its resolution of justice. However, this business model often encourages writers to default to formulaic shortcuts, prioritizing the quick resolution of the Case of the Week over meticulously structured, emotionally resonant character arcs that require true setup and payoff.

The NCIS franchise’s longevity is a testament to its formula. But for a show to thrive creatively, it must continually strive for great storytelling, not just good enough content. The misfired gun is a symbolic wake-up call, reminding the creators that even in a high-volume police procedural, the rules of dramatic writing—rules established long before the invention of the television—still matter. A great piece of fiction, whether a 19th-century play or a 21st-century TV spin-off, succeeds when it respects the audience’s investment and pays off the promises it makes.