CLEVELAND, Ohio — When the cranky old comic best known as Fred G. Sanford grabbed his heart, fell to the ground and suffered the last of the Big Ones in 1991, his colleagues busted up laughing. They thought he was pulling another, “Elizabeth, I’m coming to join you.”

But it was no joke. Redd Foxx, 69, had suffered a heart attack. Three hours later, he was dead.

It was a fitting way to go for Foxx, an actor for whom nothing was sacred. Even in death, he kept them laughing.

“He was one of the greatest and always kept people laughing,” says actor Nathaniel Taylor. “I really loved Redd.”

You might know Taylor as Rollo – the jive-talking cat on “Sanford and Son.” Yeah, that’s him: The dude in the snazzy leather jacket with the mackin’ plan.

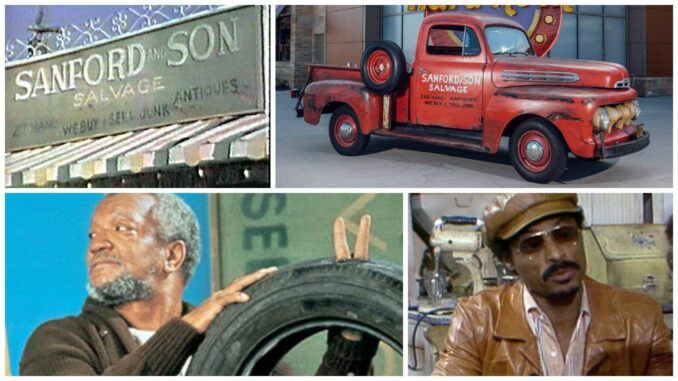

On Sunday, Rollo is coming to town. He’ll be reunited with the iconic “Sanford and Son” truck at the Hard Rock Rocksino Northfield Park. The truck, which is owned by Blueline Classics of North Royalton, was stationed at the Hard Rock this week.

Taylor will be on hand alongside the truck – a red 1951 Ford F1 — from 2-6 p.m. Sunday. For more information, go to hrrocksinonorthfieldpark.com.

“I’ll be signing autographs and talking with people about ‘Sanford and Son’ and Redd,” says Taylor, via phone from his home in Los Angeles. “I was so blessed to be on that show and it touches my heart how many people still to this day come up to me and say, ‘Hey, Rollo, man, I love you and I love “Sanford and Son.” ‘ “

It’s no surprise.

Almost four decades after the junkyard sitcom was scrapped, it remains one of TV’s most-beloved shows. Dozens of Web sites are devoted to it. It’s been the subject of scholarly writing.

“People of all ages, all walks, all races and places connect with that show, because it was about real people living under real pressures and circumstances,” says Taylor. “I took bits and pieces of people I knew to create Rollo, and we all did that with the show – because it was about humanity.”

The legacy of Fred’s empire is, no doubt, greater than junk. “Sanford and Son” was a ground-breaker.

From 1972 to 1977, the top-rated NBC show about a crotchety old junk man and his son busted down the doors for a generation of black entertainers who had toiled for years on the “chitlin circuit” — comedy’s equivalent of the Negro Leagues.

At the front of the line was Foxx.

Before he became a star on “Sanford,” Foxx was known for his raunchy party records and black-and-blue stand-up act. Before that, he was a drifter who played the washtub on street corners, slept on rooftops and hung out in Harlem with Malcolm X.

“Unlike most black entertainers, Redd never forgot where he came from,” Demond Wilson, aka Lamont, told The Plain Dealer. “Most of the characters he brought on – Aunt Esther, Bubba, Melvin — were people he had known from the chitlin’ circuit.”

Fred’s nemesis Aunt Esther was played by LaWanda Page, a Cleveland native and an acclaimed comic before she was on the show.

“Man, LaWanda was so nice and so funny,” says Taylor. “She was also so encouraging – which meant a lot to me because I was the shy guy and would usually be off to myself.”

Taylor never imagined being an actor; he was working as a lighting guy at a community theater in Los Angeles when his mentor suggested he try out for the part.

“I was in the audition room when the door opened and bumps into me, and there’s the director Aaron Ruben looking at me, and I was still wearing my electrical belt from my lighting job,” says Taylor. “So he asks if I’m the electrician here to fix some problem they had.”

Of course, Taylor told the director that indeed he was and wanted in, fidgeted around with an outlet and then admitted he came in with ulterior motives.

“He had me read a few lines and then sent me down to Redd Foxx’s room,” says Taylor. “We were both from St. Louis and started talking about that, and next thing Redd was like, ‘OK, you got the part.’ “

Rollo was born – and Instantly became one of America’s most beloved rogues.

“Man, people still come up to me and recite my lines from the marijuana episode,” says Taylor, referring to the “wild parsley” scene in an episode called “Fred’s Treasure Garden.” “The funny thing is, I was never that hip and I wasn’t much of a ladies man.”

“I had no mack and had no game and I was not at all a ladies man,” he added. “I was actually pretty shy — so imagine how I felt when I realized that I can get away with playing Rollo?”

Like a ladies man?

“Ha, I already was a ladies man – I was married and had four daughters,” says Taylor, 78, with a laugh.

The testing of social mores and send-up of race relations turned “Sanford and Son” into a taboo-breaking show that was often seen as the black counterpart to “All in the Family.”

No way, according to Wilson.

” ‘All in the Family’ was such a mean-spirited show. There was no humanity there — just a bunch of people arguing about the issues of the day. That’s why it’s so dated,” said Wilson. ” ‘Sanford and Son’ transcended politics and race. It was a show about a son and a father who had a love-hate relationship but yet needed another one to get by in life.”

The theme of the show underscores the Hard Rock Rocksino event, which takes place on Father’s Day.

“It had a degree of sophistication that got lost on a lot of people,” added Wilson.

How so?

“Well, I always hear people — black and white — saying it has a lot of racial stereotypes,” according to Wilson. “But it was the first show where black people were portrayed in a realistic setting.”

Taylor agrees and recalls how he would take elements of friends and adapt them to Rollo’s character.

“It was a father-son story that transcended race,” says Taylor. “You had Lamont, a homeboy who was very loyal to Fred and stood with him. On the other hand, Rollo was this street guy looking to get into trouble.”

Much is made of the “The Cosby Show” crossing over into mainstream white America. But “Sanford” managed to do the same while remaining irreverent – and without rolling out an upper-middle-class family that could pass for white.

“You could call ‘Sanford and Son’ groundbreaking, but it was part of a larger groundbreaking cultural movement in the 1970s,” says Taylor. “Yeah, you had TV shows like ‘The Jeffersons’ or ‘Good Times’ or ‘What’s Happening,’ but you also had ‘blaxploitation’ films that tried to depict life in black America realistically. And that’s really what ‘Sanford’ was trying to do – be realistic and be funny.”

In the world of “Sanford,” characters mix Champagne and Ripple and play losing lottery tickets while surviving amid a junkyard – a conceit you might find in an existential novel or, perhaps, a send-up of one.

“That’s what it’s all about,” says Taylor. “And, man, all these years after ‘Sanford and Son,’ I’m still smiling about it all.”