There are few roles in television history that demanded such careful balance of ideology, comedy, and contradiction as Mike “Meathead” Stivic, played by Rob Reiner on the groundbreaking sitcom All in the Family. As the liberal son-in-law to the show’s notoriously bigoted patriarch Archie Bunker, Mike was not merely a character—he was a generational counterpoint, a living embodiment of the Baby Boomer backlash against the beliefs held dear by the so-called Greatest Generation.

Set against the backdrop of the turbulent social and political shifts of the 1970s, All in the Family offered American audiences something entirely unprecedented—a sitcom that didn’t shy away from controversy, but rather embraced it head-on. At a time when network television often skirted uncomfortable truths, this show leaned into them with unflinching boldness, threading comedy through the fabric of the nation’s most divisive debates. And at the center of this cultural battleground was a single working-class household—one whose dinner table arguments mirrored those unfolding in millions of homes across the country.

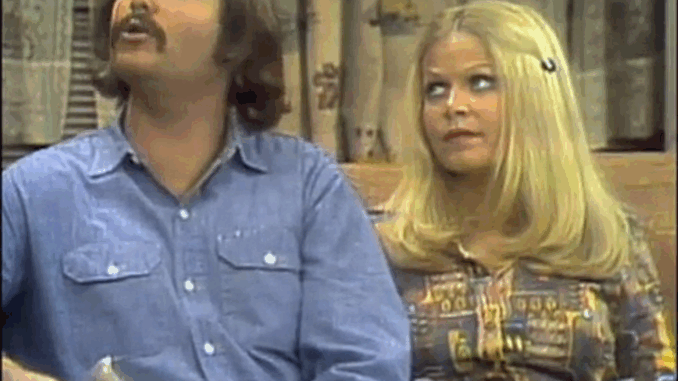

The Bunker family served as a microcosm of generational conflict. Archie Bunker, the irascible patriarch, clung tightly to his conservative worldview, laced with casual bigotry and stubborn pride. He was a relic of an earlier era—an unapologetic product of the Greatest Generation whose views were increasingly out of step with the changing world. Enter Michael Stivic—Archie’s long-haired, college-educated son-in-law—who became both houseguest and ideological adversary. A self-proclaimed liberal and ardent believer in civil rights, women’s liberation, and anti-war activism, Mike was the voice of the Baby Boomer counterculture, the living embodiment of everything Archie despised.

Yet, what made Mike truly compelling and often infuriating was the fact that he wasn’t portrayed as an untouchable moral beacon. Far from it. The brilliance of All in the Family lay in its refusal to paint its characters in black and white. While Mike may have spoken the language of social progress, his actions revealed a man still wrestling with his own blind spots and ingrained assumptions. Particularly in his relationships with the women around him most notably his wife Gloria Mike frequently veered into condescension, revealing a patriarchal streak not so different from Archie’s, just wrapped in more enlightened packaging.

Portraying this complicated mix of sincerity, arrogance, and well-meaning hypocrisy wasn’t easy, and Reiner didn’t land the part on the first try. In fact, like the show itself, it took multiple attempts before the right formula and the right casting came together.

Reiner originally auditioned for the role of Mike during All in the Family’s early development at ABC. At that point, Norman Lear’s now-legendary series had gone through two pilot episodes, both with different actors in the roles of Mike and Gloria. The show was still searching for its core chemistry, and Reiner, despite his audition, wasn’t chosen. The timing simply wasn’t right.

But fate has a curious way of circling back. Shortly after his unsuccessful tryout, Reiner found work as a writer on Headmaster, a short-lived dramedy starring Andy Griffith. The series, set in a prestigious California private school, was miles away from the blue-collar realism of All in the Family, but it gave Reiner a crucial opportunity—not just to write, but to act. In the episode titled “Valerie Has an Emotional Gestalt for the Teacher,” Reiner played a young teacher involved in an inappropriate affair with a student. Though Headmaster quickly faded into obscurity and is nearly impossible to find today, that particular performance left an impression where it counted most: with Norman Lear.

Lear, having seen Reiner’s layered portrayal of a man in a morally fraught situation, recognized something in the actor he hadn’t before—a maturity, perhaps, or a deeper capacity to handle a role as nuanced and volatile as Mike Stivic. When All in the Family was eventually picked up by CBS, a third pilot was ordered. This time, Rob Reiner was given a second chance. Alongside Sally Struthers, who was also newly cast as Gloria, he became part of the third and final iteration of the show’s core family. And this time, the pieces fit perfectly.

Reiner would later reflect on this winding path in an interview with the Archive of American Television, acknowledging that his appearance in Headmaster likely sealed the deal. Lear, he believed, saw in that performance the growth and capability needed to take on the Meathead. “I think Norman Lear saw my work in Headmaster and I auditioned again,” Reiner recalled. “He felt I had matured as an actor, I think, and gave me the part on the CBS [version of All in the Family].”

Interestingly, acting was never Reiner’s ultimate goal. From the start, his heart was in writing and directing—a passion he would eventually fulfill with great success in later years. But All in the Family offered him a platform he couldn’t have imagined. As Mike Stivic, Reiner embodied not just a single character, but a generation of idealistic white liberal men who, despite their good intentions, were still learning what true allyship looked like. He portrayed Mike’s virtues and flaws with equal weight, giving audiences someone to both root for and criticize. His performance remains a cultural touchstone—so defining, in fact, that Reiner never sought to outdo it with another onscreen role.

And what became of men like Mike as they aged? Reiner never stopped evolving. Years after All in the Family, he would go on to play a very different father—Max Belfort, the straight-talking, foul-mouthed dad of Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio) in The Wolf of Wall Street. The contrast between those two characters—idealistic young Meathead and cynical old-school Max might seem stark, but both reflect aspects of masculinity in different times, shaped by power, privilege, and ego.

In hindsight, Mike Stivic’s complexity was not only a bold creative choice—it was essential to All in the Family’s mission. By refusing to paint anyone as wholly good or entirely bad, the show forced viewers to confront their own assumptions. Through Reiner’s portrayal, we saw that even those who claim to fight for change must remain vigilant about their own blind spots. And sometimes, it takes a second audition and a few years of growing up to get it right.