Queen Charlotte: What Was Wrong With King George (And Why He’s Hidden)

In Bridgerton, King George III only appears briefly because, as in real life, the king’s illness was so severe he had to be kept hidden away.

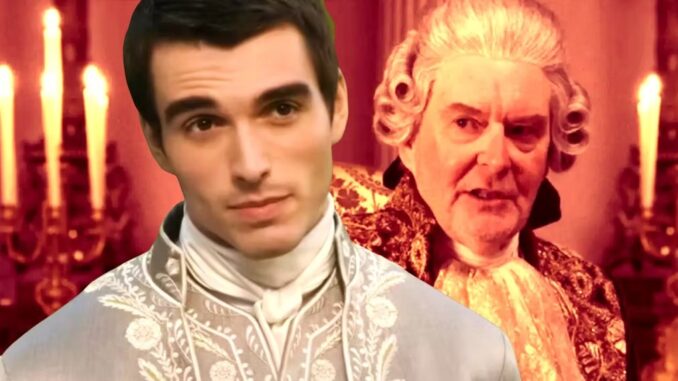

King George’s Bridgerton appearances in seasons 1 and 2 are brief, and he is mentioned infrequently – partly because he’s not meant to be a major character and partly because, by that point in time, he was simply too ill to appear publicly. Queen Charlotte, meanwhile, establishes George as a key character, of course. Played in Bridgerton by James Fleet, King George III is portrayed in the spin-off by Corey Mylchreest, in his early 20s.

King George III’s three appearances in Bridgerton are initially only relevant because of what they reveal about Queen Charlotte. The brief dinner scene with Queen Charlotte and King George III in Bridgerton Season 1 provides a somewhat true-to-life explanation for Queen Charlotte’s interest in the fictional Lady Whistledown. As soon as we see how tortured King George III has become, and how much this disturbs his wife, it becomes perfectly clear that Charlotte needs a distraction – and Lady Whistledown provides such a perfectly enveloping and delightful diversion that, at times, Queen Charlotte seems to forget her husband’s poor health. Queen Charlotte goes even further into exploring their romance and their ongoing relationship dynamic, as well as his illness.

The True Story Of King George III’s Illness

Often reductively referred to as the “Madness of King George”, George III’s psychological issues have been a matter of fierce debate over the years. What is not up for debate is the fact that George was unable to continue ruling as a monarch by the time he reached middle age. That prompted his son, George IV, the Prince of Wales to take over the king’s duties, as Prince Regent. Sadly, George III’s incoherency and instability made him a poor face for the royal family, and he was kept out of the public eye to protect the monarchy’s image, much like what is seen of King George in Bridgerton.

By King George III’s later years, he was kept confined and out of sight. Unlike what’s seen in Bridgerton, Queen Charlotte had reported stopped dining with George. She slept in a separate bedroom from George and refused to be alone with him from 1804 onward. By 1813, when Bridgerton took place, it’s believed that Queen Charlotte had stopped seeing George altogether. He suffered several extreme periods of ill-health, for a long time attributed to porphyria, and was trapped in Kew for his own good. After his final relapse in 1810, the King never recovered, and he died in 1820.

King George III’s Illness In Bridgerton

While King George III is mentioned in Bridgerton, he plays a mostly offscreen role, but his illness is very much based on historical accounts of the monarch. According to these accounts, King George III’s illness included symptoms like convulsions, frothing at the mouth, rambling incoherently, bouts of depression and, later in his life, the loss of his hearing, vision, memory, and ability to walk. After the death of Princess Amelia, George sank into a deep depression and never recovered from the loss of his favorite daughter. In 1811, King George III enacted the Regency Act, which allowed his son George IV to function as regent and become the heir. Queen Charlotte became George’s legal guardian and the king’s mental and physical health continued to deteriorate until his death in 1820.

The exact cause of King George III’s “madness” is a topic of debate among historians and physicians. Until recently, the prevailing theory was that King George III had porphyria (a rare liver disorder) and that his exposure to arsenic contributed to worsening symptoms. Although evidence for King George III having porphyria is well-documented, and the theory is still widely accepted, conflicting theories have emerged in recent years. In the last decade or so, scientists, doctors, and historians have posited that King George III did not, in fact, have porphyria, but instead had some combination of bipolar disorder, chronic mania, and dementia. Dr. Peter Garrard of St George’s, University of London [via BBC]. went so far as to call the theory dead, saying:

The porphyria theory is completely dead in the water. This was a psychotropic illness.