“His shows are what started the conversation about race and justice — All in the Family, The Jeffersons — in a way that America had not been prepared to [discuss] before. His impact and his legacy will be felt for generations to come. Even people who are not familiar with his shows are experiencing the benefits of what those shows did for us as a culture.” – Oprah Winfrey

By 1974, television had been America’s primary source of entertainment for more than two decades. They had seen Black people portrayed as “inferior, lazy, dumb, and dishonest,” as the NAACP complained about The Amos ‘n Andy Show in 1951, and as domestic servants in Beulah. The ‘60s brought non-stereotypical, professional characters like Julia, a widowed nurse raising a young son, and Pete Dixon, the idealistic high school history teacher of Room 222.

But America had not seen a stable, loving, two-parent Black family on television until the sitcom Good Times hit the airwaves on February 8, 1974.

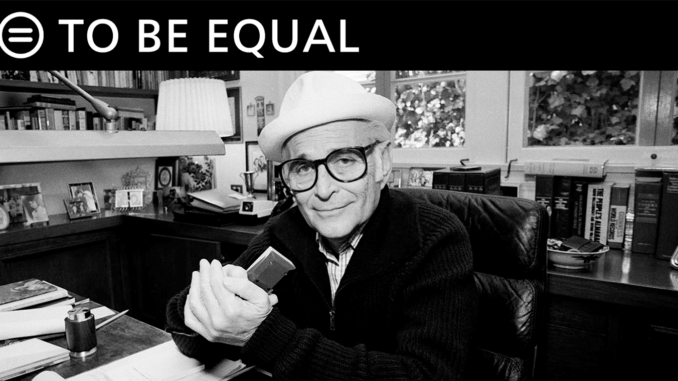

Norman Lear, the executive producer of Good Times and other groundbreaking shows, died earlier this month at the age of 101, leaving a legacy that is unmatched in its impact on white America’s perception of Black families.

“There wasn’t a Black person who could have made that happen,” filmmaker Tyler Perry told the New York Times. “It had to be Norman Lear.”

Lear’s influence on a generation of young, Black creators like Perry may be his greatest legacy.

Kenya Barris, who created the show black·ish, said, “It’s like asking someone who played basketball if Michael Jordan influenced them.”

As well-intentioned as Lear may have been, he was known to fumble. Good Times attracted its share of criticism. Actor John Amos, who portrayed family patriarch James Evans, complained that the storylines devised by the show’s white writers were unrealistic and the character of J.J. was buffoonish. Amos’ character was killed off two years into the series’ run.

When the Black Panthers complained to Lear, “Every time you see a Black man on the tube, he is dirt poor, wears sh*t clothes, can’t afford nothing … That’s bullsh*t,” Lear responded by creating The Jeffersons.

The Jeffersons featured not only television’s first prosperous Black family – who famously “moved on up” from working-class Queens to Manhattan’s swanky Upper East Side – but also its first prominently-featured interracial married couple, Tom and Helen Willis.

Less remembered, but equally groundbreaking, The Jeffersons was the first sitcom to address controversial subjects like colorism and transgenderism. The Willis daughter Jenny was shown to be resentful of her lighter-skinned brother who could pass for white. George Jefferson’s Army buddy, “Eddie,” underwent gender reassignment surgery and transitioned to life as “Edie.”

Born and raised in Connecticut, Lear was inspired to a lifetime of social activism when he first heard a broadcast by the antisemitic demagogue Father Charles Coughlin, “the father of hate radio.”

Lear told Variety that “the feeling of this creeping hatred and racism” of the Trump era recalled Coughlin’s broadcasts in the early 1930s. In 1981, in the wake of the election of President Ronald Reagan, Lear founded the advocacy group People for the American Way.

The American way, according to Lear, is pluralism, individuality, freedom of thought, expression and religion, a sense of community, and tolerance and compassion for others.

As People for the American Way President Svante Myrick said in his tribute to Lear, “We will honor Norman by carrying on the work to which he dedicated so much of his life.”