The “All in the Family” producer made sitcoms into a form of patriotic dissent.

In 1942, Norman Lear signed up to fight the fascists. He served as a radio operator and gunner in a B-17 bomber named “Umbriago” by its crew, after a catchphrase of the comedian Jimmy Durante. As Lear watched bombs spill out of the plane’s belly over Germany, he said in a 2021 interview with the Yiddish Book Center, his attitude was “Screw ’em.” But there was also a complicating empathy: “I remember thinking, imagining a table of family, of Germans, sitting around the table as the bombs dropped.”

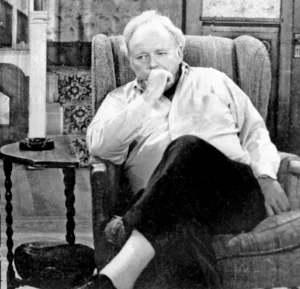

Lear, who died Tuesday at age 101, was hardly alone in volunteering to fight for his country in World War II. What distinguished his career as a TV producer was how he fought for his country in his sitcoms.

The most famous of them informed Americans that there was a war going on at their own kitchen tables. By January 1971, when “All in the Family” premiered, TV had been spilling a gusher of reality into living rooms — Vietnam, street protests, the Kent State shootings — but sitcoms had remained an alternative universe of goofy castaways, friendly witches and lovable millionaire bumpkins.

“All in the Family,” which Lear had spent years trying to develop for the networks, personified the country’s conflicts under one roof, at 704 Hauser in Queens. Archie Bunker (Carroll O’Connor), the racist, reactionary dockworker, was the choleric face of the kind of blue-collar workers, alienated by social change, who had attacked antiwar demonstrators in the “hard hat riots” the previous spring. He sparred with his feminist daughter, Gloria (Sally Struthers), and her leftist husband, Michael (Rob Reiner), while his anxious wife, Edith (Jean Stapleton), tried to keep an increasingly elusive peace.

Lear designed “All in the Family” to air arguments audiences weren’t hearing in escapist sitcoms. (Other sounds too: The pilot episode featured, for the first time on network TV, the noise of a flushing toilet—“terlet,” in Archie-speak — which was the show’s shot heard ’round the world.) Its format was theater-like, its dialogue rough and real, its comedy smart but not highbrow. It was a lightning revolution, claiming the No. 1 spot in the ratings and holding on for five years.

“All in the Family” was based on a British series, “Till Death Us Do Part.” The title of the original refers, of course, to wedding vows — that is, to the relationship between two people. The title “All in the Family” expanded that outward. The troubles were in our family, the fights were in our family, the racists were in our family. We were bound to them.

So Archie Bunker, for all his prejudice and bullheadedness, had to be vivid, alive, funny. Yes, there was a risk that audiences would laugh with his bigotry and not at it. But if you couldn’t like him, you couldn’t see how any of the other characters could love him. And if you couldn’t see that, then you couldn’t see the Archie in any of the people that you loved.

Lear’s connection to Archie was intimate. His own father, he told NPR, was “a bit of an Archie Bunker,” given to using racist language, and Lear based the character in part on him. But Archie was also, like Lear, a World War II veteran who had been based in Italy with the Army Air Forces.

Archie was an oaf and a bigot, but a richly human one. Lear’s depiction of him was — like much of his TV work — a critique that came from love. He imagined popular, populist TV as a form of patriotic dissent, embodying a spirit of big-hearted 20th-century liberalism.

Part of that philosophy, in Lear’s subsequent work, was opening the doors to other members of the American family whom Archie deplorably deplored from his favorite chair. He made TV about rich Black people (“The Jeffersons”) and working-class Black people (“Good Times,” “Sanford and Son”), about feminists (“Maude”) and divorced women (“One Day at a Time”) and dissatisfied housewives (“Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman”). He tried to establish a Latino family sitcom with the short lived “a.k.a. Pablo,” and later in life executive produced a reboot of “One Day at a Time” centered on a Cuban American family.

Lear was inspired in part, he said, by his own minority experience as a Jew in America, in the era of the antisemitic radio demagogue Father Charles Coughlin. In his TV work Lear built a counter-weapon, a bigger and better soapbox.

But he also made distinctive art. He created a bracing comedy language, able to play to both the cheap seats and the opera boxes. As successful as many of his shows were, they weren’t as widely imitated as their more feel-good contemporaries. Decades later, when someone attempts a show with a similar provocative spirit and theater-for-the-masses style — say, NBC’s “The Carmichael Show” a few years ago — Lear’s is still the first name that comes to mind for comparison.

His work also managed to stay relevant, even prescient, a half-century later, as became obvious with the presidency of Donald J. Trump, whose Queens bluster and bigoted “Those Were the Days” grievances echoed Lear’s most famous character. In 2017 — the same year that Lear refused in protest to attend a Kennedy Center reception at the White House — the former presidential adviser Steve Bannon said admiringly of the president, “Dude, he’s Archie Bunker.”

That an alt-right agitator could liken his chosen candidate to the character Lear wrote as a pigheaded buffoon — and see it as not just a compliment but an asset — could, you might argue, be the ultimate indictment of Lear’s gamble in making Archie likable.

But that approach also allowed Lear’s voice, his patriotic belief in pluralism, to carry in places where a stump speech wouldn’t. My own father was a blue-collar World War II vet who, like Lear’s, had a little Archie Bunker in him. Maybe more than a little. Yet when I was a kid, we’d watch “All in the Family” together.

I doubt that laughing with and at Archie did much to change my dad. But I think it helped shape me. “All in the Family” talked back, in a way I couldn’t as an elementary-school kid. It showed me that there were other points of view and that millions of other people were interested in the argument.

I don’t know if Norman Lear ever imagined the inside of a house like mine when he created his shows, the way he pictured the families inside German homes when he served in the war. But the same principle applied: Family life may be private, but it’s never insulated from the forces troubling the world. With his work, he tried to drop something into American living rooms that might, at least, leave us a little bit better. Thank you for your service, Mr. Lear.