“Good Times,” “The Jeffersons” and “Sanford and Son” brought a wave of Black characters to TV, even as the shows opened up tensions over stereotypes.

As a birthday present for Tyler Perry last year, a mutual acquaintance arranged for him to meet one of his heroes, Norman Lear. Perry grew up watching Lear’s groundbreaking television shows, and was awed by how several presented a fuller version of Black lives onto American television screens for the first time.

Long ago, Perry had hoped to have a storied career that would emulate a speck of what Lear’s shows such as “Good Times” and “The Jeffersons” displayed: that Black people can share opinions, fall in love, laugh and be fearful just like anyone else.

“Had it not been for Norman, there wouldn’t have been a path for me,” said Perry, whose film and TV empire has made him one of the most powerful figures in Hollywood. “It was him bringing Black people to television and showing the world that there’s an audience for us.”

Perry departed his meeting with Lear, who was 100 years old at the time, with a deeper appreciation for the craftsmanship of the pioneering television writer and producer who died at 101 on Tuesday. The reality of Lear, a white man, being responsible for bringing a fuller picture of Black lives to American TV screens was a product of the era, when most doors were still closed to Black producers and creators. Some characters in his shows were the source of flare-ups, particularly when some Black cast members complained about stereotypical portrayals, which are still debated today.

Yet despite those tensions, it’s hard to find anyone in the medium of television who is held in such high regard, including by many Black writers and showrunners now creating and running today’s shows.

“It’s like asking someone who played basketball if Michael Jordan influenced them,” said Kenya Barris, the creator of “black-ish.” “He changed the way contemporary storytelling was told in the genre that I was doing it in.”

Barris said that Lear was an early champion of “black-ish” and even visited its writers’ room in 2016.

“It’s about as impactful in modern media as a legacy could be,” Barris said of Lear’s body of work that made him a defining figure of ’70s TV.

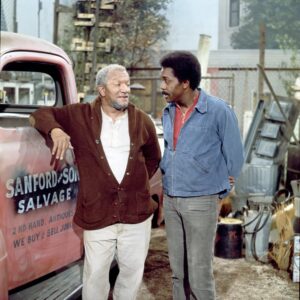

Lear’s shows touched on hot-button issues such as civil rights activism, alcoholism and abortion, going far beyond the one-dimensional existence that Black characters were previously relegated to. His shows depicted television’s first two-parent Black family, an upwardly mobile Black family and the other side of the coin to his most famous character, “All in the Family’s” Archie Bunker, in Redd Foxx’s portrayal of the oft-bigoted Fred Sanford in “Sanford and Son.”

This full-rounded view of Black life in America — through characters who had failures and triumphs, struggles and aspirations — helped usher in what historians call the era of “social relevance” in television, in which TV shows and sitcoms offered more authentic depictions of Americans’ lives, said Adrien Sebro, an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin and author of “Scratchin’ and Survivin’: Hustle Economics and the Black Sitcoms of Tandem Productions,” a book about Lear’s many television productions.

Beverly McIver, an artist and professor of art history and visual studies at Duke University, remembers watching Lear’s shows every week as a child. Growing up in a housing project in Greensboro, N.C., she identified with J.J. Evans, the teenage aspiring artist who grows up in Chicago public housing, portrayed by Jimmie Walker on “Good Times.”

“These shows gave me hope that I could rise out of the project, not continue the cycle of poverty, and that I could be an artist,” she said.

Walker, in an interview, said Lear always looked to deliver a message through his shows, which initially threw Walker.

“Norman, if you want to deliver a message, go work for Western Union,” Walker, 76, recalled telling Lear. “I’m here to work. I’m here to have fun, baby. I’m here to do comedy.”

But Walker eventually grew to appreciate Lear’s stance in delivering social commentary through comedy.

“He wasn’t a funny-joke writer guy,” Walker said. “He believed that both sides needed to be heard.”

Fresh from the Civil Rights era, Hollywood had yet to open itself to Black shows, let alone Black showrunners.

“There wasn’t a Black person who could have made that happen,” Perry said of the fuller portrayal of Black life onscreen. “It had to be Norman Lear.”

He added: “It had to be a person who understands humanity and people and who we all are at our core and the things we all appreciate and care about, which are family and love and that we all feel pain.”

Lear and other producers held tight to creative control of the series. As groundbreaking as the shows centering Black characters were, the creative decisions were still being made by white people who did not share the experiences of the cast onscreen.

Two Black writers, Eric Monte and Mike Evans, are credited with creating “Good Times,” but have struggled to receive recognition for their contributions. Monte also argued that Lear stole his idea for “The Jeffersons.” He received a $1 million settlement and said he was eventually blacklisted from Hollywood.

“Everything they wrote was stereotypic,” Monte told The Philadelphia Inquirer in 2006.

But many who worked with Lear credited him with changing their lives.

“I’ve had a very interesting life being on ‘Good Times,’” said BernNadette Stanis, who played Thelma Evans. “My whole life as an adult has been attached to ‘Good Times.’”

Other actors who worked on Lear’s shows recalled him extending an open ear to their ideas and thoughts. Marla Gibbs once asked Lear why he seldom showed up on the set of “The Jeffersons.” Gibbs recalled Lear saying that the cast and show were doing just fine without him.

But if she ever needed him, Lear added, he’d be there.

Gibbs, who played the Jeffersons’ wisecracking maid, Florence Johnston, requested him shortly after. The show’s actors lobbied Lear for a more rounded depiction of the Willises, portrayed by Roxie Roker and Franklin Cover as television’s first interracial marriage between Black and white partners. As a result, the pair exchanged a kiss in a landmark 1974 episode.

Beginning in 1972, NBC aired Lear’s “Sanford and Son,” which starred Foxx and Demond Wilson as a father and son in Los Angeles, and in 1974 CBS aired “Good Times,” which focused on the Evanses — the first time a Black nuclear family appeared on television.

The show was originally envisioned as starring a one-parent matriarchal household, but Esther Rolle, argued that her character, Florida Evans, should be married. Stanis recalled Lear listening to Rolle and, soon after, hiring John Amos to play her husband, James.

“He was lenient in that way,” Stanis said.

With Rolle’s backing, Stanis talked to Lear and the show’s other producers and writers about establishing more of a voice for Thelma, the daughter of the household.

“We were the first Black family show,” Stanis said. “You would have 50-, 60-year-old Caucasian men writing for a teenager and they didn’t have much to say about me.”

She added: “Norman was there, the producers and the writers, all of them, the director, everybody was there. They received my viewpoint very well.”

That was not the case with every conflict. A 1975 article in Ebony magazine titled “Bad Times on the ‘Good Times’ Set” described a “continuing battle among the cast members to keep the comedic flavor of the program from becoming so outlandish as to be embarrassing to Blacks.”

The actors grew particularly frustrated with the outsized role of Walker’s J.J. as the loud and often lazy son with the famous catchphrase of “dyn-o-mite!” who became enormously popular with audiences.

Cast members believed the performance portrayed Black Americans in a stereotypical lens. Despite these concerns, the show’s writers transformed J.J. from a minor character into one of the show’s central figures.

“I thought too much emphasis was being put on J.J. and his chicken hat and saying ‘dy-no-mite’ every third page,” Amos said in a 2014 interview with the Television Academy. He added that producers resolved the conflict by getting rid of Amos’s character. “So they said, ‘Tell you what? Why don’t we kill him off and we’ll all get on with our lives?’”

In addition to Amos’s firing, Rolle also left the show for a season before returning.

“When we found out that John wouldn’t be back, we read the script and I thought it was mistaken identity,” Stanis said, adding that when Rolle, who died in 1998, briefly left, “I don’t think that she was very happy with having to leave the show the way it was designed.”

In his 2014 autobiography, “Even This I Get to Experience,” Lear wrote that members of the Black Panthers came to his office to complain that “Good Times” perpetuated stereotypes about Black poverty. Lear responded with “The Jeffersons,” which debuted on CBS in 1975. The show featured Sherman Hemsley as George Jefferson, a Black man with a successful dry-cleaning business and a luxury apartment in Manhattan, and Isabel Sanford as his beleaguered wife, Louise.

Gibbs broke out as Florence before going on to a long career that included roles on series like “227” and “The Hughleys.” When she received her star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2021, Lear accompanied her to the ceremony. She remembered him saying that laughter adds years to one’s life and thanked her for adding years to his.

“I’d say without Norman, people would not know my name,” said Gibbs, 92. “He hired me and because of the affiliation, everybody knows Marla Gibbs and they know Florence, so I’d say he definitely added years to my life.”