In the world of Sanford and Son, most of the attention went to Fred G. Sanford — loud, stubborn, crude, and impossible to ignore. But it was Lamont Sanford, played with quiet brilliance by Demond Wilson, who carried the emotional weight of the show. While his father hurled insults and faked heart attacks, Lamont was fighting a subtler battle: the push to define his own identity as a modern Black man in a world that expected him to stay exactly where he was.

This wasn’t a sitcom about a junkyard. It was a sitcom about a generational crossroads — one that countless real-life sons and fathers were navigating in the 1970s. And no one symbolized that tug-of-war more poignantly than Lamont.

More Than a Straight Man

At first glance, Lamont seemed like the classic sitcom “straight man” — the grounded, rational foil to his eccentric father. But Sanford and Son gave him much more depth. He wasn’t just reacting to Fred’s chaos; he was quietly carving out his own philosophy. Lamont represented a generation of young Black men who were raised in working-class environments but dreamed of education, financial freedom, and emotional independence.

Week after week, viewers watched him wrestle with the paradox of loving his father but wanting more than a life spent sifting through other people’s garbage. He quoted Shakespeare, studied psychology, and kept one foot in the cultural sophistication he craved — even while surrounded by rusted toasters and broken radios.

Yet no matter how hard he tried to rise above the junkyard, something always pulled him back.

The Guilt That Binds

At the core of Lamont’s struggle was guilt. Fred Sanford was a master manipulator, using illness, nostalgia, and loneliness as emotional leverage. “You want to leave your poor old daddy to rot in this junk heap?” he’d wail, hand clutched to his chest. The audience laughed, but for Lamont, it was a trap — one that millions of viewers, especially Black men, recognized all too well.

Lamont wasn’t just battling Fred; he was battling the voice of an entire older generation telling him to be grateful, to stay close, to honor the sacrifices that came before. And that pressure weighed heavily. Each time he tried to leave, to date someone new, or to start a business, Fred would pull him back — not with violence, but with guilt, love, and sarcasm.

The show’s brilliance lay in never giving Lamont an easy exit. He wasn’t portrayed as weak, but as torn — a man caught between the duty to his father and the dream of his own life.

A Mirror for Black Audiences

Lamont’s journey wasn’t a Hollywood fantasy. It reflected a reality many Black families were living. During the 1970s, more African Americans were going to college, entering white-collar professions, and moving into suburbs — yet family roots often remained in urban, working-class neighborhoods. That created a cultural and emotional gap. And Lamont stood in that gap every episode.

Unlike many sitcom characters of the time, Lamont wasn’t a buffoon or a caricature. He was thoughtful, frustrated, hopeful — a man trying to figure things out without hurting the people he loved. In that sense, he wasn’t just a fictional son. He was a cultural stand-in for a new kind of Black masculinity: introspective, aspirational, but never disconnected from heritage.

The Limits of the Sitcom Format

Still, the constraints of network television in the 1970s meant Lamont’s development was often reset at the end of each episode. Just when it seemed like he might finally break free — through a new girlfriend, a business idea, or even a trip — the sitcom format reeled him back into the same old living room, with Fred back in his chair, sipping Ripple.

But those resets didn’t erase what Lamont represented. In many ways, his failure to escape the junkyard made him more relatable. Most people don’t have clean narrative arcs. They try, they stumble, they try again. That’s why Lamont’s story still resonates — because it’s not a success story or a tragedy. It’s something more real: the ongoing process of becoming.

The Legacy of Demond Wilson’s Performance

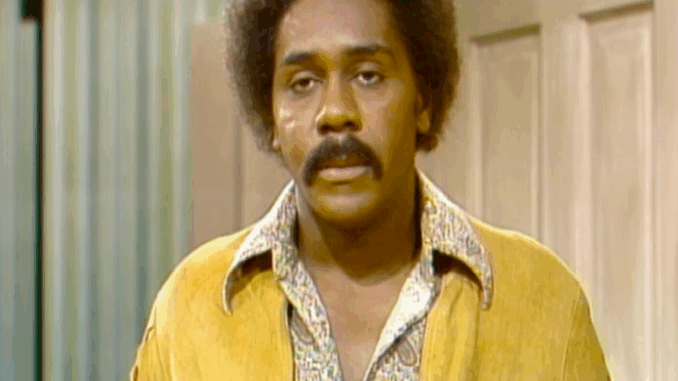

Demond Wilson rarely gets enough credit for what he brought to Sanford and Son. Holding his own against a comedy titan like Redd Foxx was no small feat. But Wilson did more than just match Fred’s energy — he provided a quiet dignity that anchored the show.

Wilson’s performance captured all the contradictions of a man trapped by love. His facial expressions told stories words didn’t. His silences spoke volumes. In one moment, Lamont might explode in anger; in the next, he’d soften, touched by Fred’s vulnerability. It was a layered, deeply human performance — one that remains underrated in sitcom history.

Off-screen, Wilson later left Hollywood and became a minister. Perhaps it’s no surprise. Lamont always seemed like a man looking for peace, trying to navigate a chaotic world with purpose.

Conclusion: The Son Who Stayed

In the final episodes of Sanford and Son, Lamont never moved out. He never started a new life or struck it rich. He stayed. And for some viewers, that was a disappointment. But for others, it was honest.

The story of Lamont Sanford wasn’t about escape. It was about balance. How do you honor where you come from without losing who you are? How do you grow when the people you love want you to stay the same?

That question lingers today. And Lamont’s quiet, determined effort to answer it — with grace, humor, and heart — is what makes Sanford and Son timeless.