Kevin Costner’s New Show Is More Than “Dallas” With Horses

In the new Western drama Yellowstone, Montana acts as the backdrop for century-old fights over what land means and who gets to claim it.

In the opening episode of Yellowstone — whose two-hour premiere debuts tonight on the Paramount Network — there are plenty of phrases that will make a Montanan chuckle. In one of the first scenes, two lawyers (one the son of a rancher who owns the biggest ranch in Montana, the other representing the interests of a rich, oily developer) are fighting over the right to claim eminent domain to build a housing tract.

The area they’re fighting over is within easy driving distance from Bozeman — the fastest-growing city in Montana — where, as in the real Bozeman, one of the primary tensions is over development. The developer aims to build a planned development with lots of stainless steel appliances and floor-to-ceiling windows, abutting the Dutton family ranch, which is, as one character puts it, “the size of the state of Rhode Island.”

But the Duttons aren’t having it. The court rules in the family’s favor, and the Dutton son tells the opposing lawyer that, instead of trying to expand near their land, they should just build upward. “Condos,” he suggests. “Condos?” the opposing lawyer replies, bewildered. “Who wants to live in a condo in Montana?”

That line tells us much of what we’re meant to know about Montana and its significance in the national imagination. Outside of Alaska, Montana is the closest the US gets to a last frontier — that mythical space where men (and they are almost always men) get to act out their fantasies and vanquish their anxieties. It’s a place where you go to seek the reverse of population density. It’s an antidote to urbanness, a place of open land — 147,040 square miles of it — but with just over 1 million people inhabiting it. It’s a place whose unofficial slogan is “The Last Best Place.” And in Yellowstone, the state of Montana becomes a tapestry on which to play out much larger questions concerning the future of land, ownership, and identity in the United States.

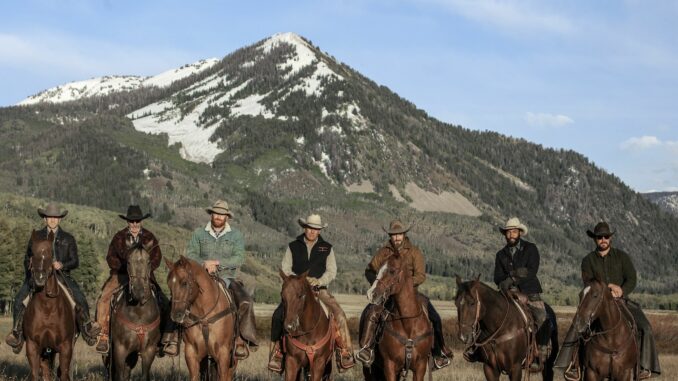

Yellowstone is slicker, more staged, and more tightly plotted than real life. But that doesn’t mean that the tensions animating the heart of the show, and the anger, defensiveness, and ardor they induce, aren’t real. The story rotates around a Montana ranching family headed by John Dutton (Kevin Costner, appropriately face-tanned, wearing an unbelievably well-washed puffy jacket) and supported, in various ways, by his four children. There’s the dutiful eldest (Dave Annable), a cowboy who’s stayed on the ranch; the feminized lawyer (Wes Bentley), who you know is his father’s least loved because he wears a suit and slicks back his hair; the sexually voracious, ballbusting sister (Kelly Reilly); and the youngest, Kayce (Luke Grimes), most beloved because he’s the hottest and the best on a horse, but also because he’s turned the farthest away from his father, marrying a Native American woman and making his home on the (fictionalized) Broken Rock Reservation with their son.