He put up his own money—and property—to make a grand western epic. Now, Costner reveals what’s at stake with Horizon, and why he had to leave Yellowstone to make it.

Sometimes Kevin Costner imagines that he’s watching himself in a movie about Kevin Costner. He pictures himself in a theater; it’s dark and he’s gazing at himself in the same way we have over the years, rooting for him to succeed. In times of embattlement or stress, he says, “I’ve got to be my own movie.” In Westerns, Costner’s preferred genre, the hero tends to ride in, outmatched and outgunned, only to come away victorious. This often seems to be the way Costner sees himself too. Famously, Costner’s first big break as an actor was cast in 1983’s The Big Chill; then, after shooting, all his scenes were cut. Before he was dropped from the movie, “I had all my friends going, ‘Kevin, you’re in that movie. You should do press. You should ride this wave,’ ” he told me. “And I said, ‘No. It’ll be a more interesting story once I do what I know I’m going to do.’ ”

Costner is a lifelong devotee of the hard way. When Ron Shelton cast the actor in 1988’s Bull Durham, he tried to hand Costner the part, only for Costner to insist on auditioning anyway. “So we went from having lunch to the batting cage on Sepulveda with a bunch of quarters,” Shelton told me. “And we’re putting quarters in there and he’s hitting line drives right-handed and left-handed, and we’re playing catch in the parking lot. Girls are walking by him. They don’t know who he is. Three months later, they’re going to know who he is.”

A few years after Bull Durham, once Costner had become one of the biggest stars in Hollywood, he used every bit of leverage he’d accumulated to produce, direct, and act in a movie most studios didn’t want: Dances With Wolves. “I had a chance to do The Hunt for Red October for more money than I’d ever seen,” Costner said. “I feel like Gollum with the ring. I thought, Oh my God, I’m going to take that ring. But I made this promise that I will go do this movie. I had to watch my own movie.” When Dances came out, in 1990, it was nominated for 12 Academy Awards and won seven, including best picture and best director.

Costner is now 69. In the past decade, he has experienced a revival of arrangements, doing nuanced and charismatic character work in film after film while starring on Yellowstone, the most popular show on television. Other actors might be content with their late-career good fortune. But other actors are not Kevin Costner, who is prone to obsession, regardless of what that obsession may cost. “I’m so grateful that I’ve never seen a UFO,” Costner said. “I’m a pretty sane person, although some people would think maybe something else. But what happens once you see one? You can’t let it go.”

One of those obsessions is a Western called Horizon, which Costner—as cowriter, director, and star—has been trying to make since 1988. Over the past 36 years, the story has evolved, from a two-hander about a couple of guys to a vast, panoramic portrait of the founding of a town—called Horizon—during a particularly bloody chapter of America’s western expansion, but Costner has never fully left it alone. In 2003, he was going to make Horizon with Disney, but the director and the studio were $5 million apart on the budget, and so Costner—never one to compromise on something he considered important—walked away. Then, in 2012, Costner picked the script up again and, with the screenwriter and author Jon Baird, turned it into four scripts. “And what’s ironic, or if not ironic, maybe a better word is what is typical of me,” Costner said, “is that if my psychiatrist looked at me and they said, ‘Kevin, let me get this straight. Nobody wanted to make one, right? At least at that point when you stopped, they didn’t want to make it?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ And she went, ‘Why do you then go out and write four more? Why do you go and do that?’ And I guess the answer is: Because I believe. But I can also see that psychiatrist going, ‘Yeah, but no one wanted one, and you just did four.’ As if I didn’t hear her the first time. And I can’t defend that psyche. I can’t defend anything other than the story just kept getting better and better for me.”

But if no one in Hollywood wanted to make one, they certainly didn’t want to make four. And so Costner, a few years ago, decided to fund the film himself, with the help of two outside investors whose names he will not disclose. (More recently, Warner Bros. has also come aboard for the first two films, handling theatrical distribution.) Press reports have been widely-eyed about just how much Costner has put on the line to make the film. “I know they say I’ve got $20 million of my own money in this movie,” Costner told me. “It’s not true. I’ve got now about $38 million in the movie. That’s the truth. That’s the real number.”

Even before production began on Horizon: An American Saga – Chapter 1 in the summer of 2022, in the vast wilderness of Utah, Costner was facing some setbacks. In 2021, he lost both of his parents. Not long after, he began to have issues agreeing on a shooting schedule for Yellowstone, issues that eventually spiraled into a contract dispute and a messy—and, until now, one-sided—argument in the press between Costner and the show’s cocreator Taylor Sheridan , as well as the production companies Paramount and 101 Studios. Last year, Costner’s wife of 18 years, Christine Baumgartner, filed for a divorce. Somehow Costner, throughout all of this, found a way to make not one but two Horizon films. And soon, he and Warner Bros. will embark on a risky and grandiose experiment that has never really been tried before, releasing both films in one summer, with Horizon: An American Saga – Chapter 1 coming to theaters in June, followed by Chapter 2 in August.

“There’s a lot that has happened,” Costner told me this spring at the home near Santa Barbara, California, where he helped raise the three youngest of his seven children. He was once again seated in the theater of his mind. “I’m right now looking at myself in the dark and going, Are you going to fucking stand up and finish? Get up. I’m the audience. Get up, Kevin. Get the fuck up and deal with this and find the joy every day of seeing your kids play while you’re here—and then work your ass off to get this thing finished.”

In August 2022, when the filming of the first Horizon began around Moab, Utah, among a series of red rocks by a muddy river, people were passing out from the heat; by November of the same year, when I visited the set, winter was already rolling in, and Costner was racing to finish production before the snow arrived. Early one frigid morning, the crew was clustered high up on Mount Peale, in the La Sal range, around a base camp reached via a dirt road that wound past grazing cattle and scrub brush, pine, and then ghostly white aspens, snow appeared on the ground as we passed 8,000 feet. In a muddy stand of trees, trucks and vans and catering trucks were clustered together; just beyond was a little wedge of ridge, overlooking a green valley, that Costner had considered perfect for the scene he was about to shoot between his character, Hayes Ellison, and a woman on the run, Marigold, played by Abbey Lee.

In August 2022, when the filming of the first Horizon began around Moab, Utah, among a series of red rocks by a muddy river, people were passing out from the heat; by November of the same year, when I visited the set, winter was already rolling in, and Costner was racing to finish production before the snow arrived. Early one frigid morning, the crew was clustered high up on Mount Peale, in the La Sal range, around a base camp reached via a dirt road that wound past grazing cattle and scrub brush, pine, and then ghostly white aspens, snow appeared on the ground as we passed 8,000 feet. In a muddy stand of trees, trucks and vans and catering trucks were clustered together; just beyond was a little wedge of ridge, overlooking a green valley, that Costner had considered perfect for the scene he was about to shoot between his character, Hayes Ellison, and a woman on the run, Marigold, played by Abbey Lee.

Howard Kaplan, one of Costner’s producers, was standing outside Costner’s trailer. “This is John Ford stuff,” he said, shaking his head. There was a little circle of chairs set up for socializing, a rubber bucket labeled “Bear Spray,” and a small crowd of people who needed answers standing at a respectful but close distance. Some nights Costner wouldn’t even bother to come down from the mountain, Kaplan said. He’d sleep in the trailer, barbecue outside, look at the stars. “I kind of just kept dreaming about the movie,” Costner told me later.

Costner emerged and walked purposefully to the strand of rocks that had been prepared for the scene, in which Hayes and Marigold stopped for the night after fleeing some evil men, and argued as they prepared to bed down. He and Lee, her golden hair in the fall light, began to rehearse and block the scene. Costner ran through his lines: “You’re not taking the full measure of this, Mari,” he said to Lee, trying to explain the danger they were still in. He paused. “If we could do one without talking,” Costner said sternly, in the direction of the crew. “I hear people.” The actor Octavia Spencer, who has worked with Costner twice, in 2014’s Black or White and 2016’s Hidden Figures, told me that in her experience, other actors and crews related to like collaborating with Costner “because he shows up on time, ready to work . He’s all business when he’s on the set, meaning everything’s efficient, you move along, the crew isn’t sitting around waiting for hours. You are working.”

Finally satisfied, Costner beckoned me over while the cameras reset. An assistant handed him a white binder with the script in it, and he reviewed his lines while we talked. “Don’t worry,” he said, when I asked if he wanted to prepare in peace. “I’ll just tell you to fuck off.” At a distance, he’d looked a little weather-beaten, another piece of American granite on the hillside, but up close he looked remarkable like the guy from the first movie I saw him in, 1987’s No Way Out: eyes still piercing, twinkling a little despite the grit. “We’re trying to thread needles now that we might get pushed off this mountain,” he said.

Every decision he made here had personal financial implications. “It’s kind of an independent movie,” Costner told me, while still studying the script. “My wife and I knew we were going to finance it. We just mortgaged a property, a beachfront property in Santa Barbara. Ten acres. I said, ‘It’s a good deal.’ And she said, ‘Yeah, one more and we’re out of business.’ ”

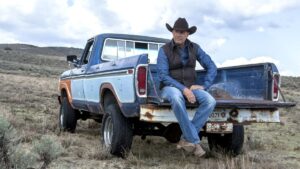

Horizon’s director of photography, J. Michael Muro, signaled that they were ready to shoot. Costner went over and stood on his mark. What was remarkable, then, was how little he did. Even from the very beginning of Costner’s career, he had this ability, to stand in front of a camera and do practically nothing. And yet the camera picks up…something. In his early days, it was a kind of wistfulness, or repressed anger, or barely suppressed mischief; more recently, he has specialized in playing hypercompetent, slightly weary men who have a task to complete, whether they want to or not. But what you see, watching him act from just a few feet away, is hardly anything at all. He simply trusts the camera will find it. “Everybody thought Brando did a little bit, but he was actually doing a lot,” Costner told me. “I’m not comparing myself to Brando, but if you watch him, there’s a lot that he’s doing. He’s moving with his hands a little bit. Just a little bit. But that’s a lot.” Shelton compared Costner to Spencer Tracy, quoting Tracy’s longtime companion: “Katharine Hepburn said, even though they were lovers, she could never tell when they said ‘Action’ because his acting just sort of flowed in and out of the scene, and you never knew when he was doing the script and when he was just being himself. Kevin is naturally like that.” Miller said that sometimes, when Costner was directing, the cast would gather just to watch him wander on camera and move props around: “He’d be in his double denim and he’d walk in front of the lens to move an ashtray and the screen kind of sets on fire. We’d all sit around the monitor, chuckling.”

Costner has played many parts over the years—ballplayers, executives, wise dads—but as a director (Horizon is his fourth film, after Dances With Wolves, The Postman, and Open Range), he returns over and over again to the American frontier , where everyone has a secret and no one is entirely known. “I’m haunted by the interactions of people when there’s no law; when something’s wide open, how do you behave?” Costner said. “And it’s a really interesting way to measure yourself in the dark. Who do I think I am in this? Now, a lot of people go, ‘Well, of course I’m the fucking hero.’ And you want to say, ‘Really? Are you sure about that?’ ”

The crew broke for lunch, and then restaged a little higher up the mountain, at a cabin purpose-built as the home of the Sykes family, the apparent villains of the first film. Costner, who had changed out of his character’s clothing into a black puffy coat, blue jeans, a blue beanie, and giant boots, was planned to direct a scene in which the dead body of one of the Sykes brothers is returned to the family compound . Two newly arrived men, friends of Costner’s, looked on, wearing Under Armor crewnecks and oxford shoes, despite the terrain. The newly fallen snow around the house had already been trampled into two feet of wet mud, and Derek Hill, the production designer and longtime Costner collaborator, was distraught—they’d have to wait for another day of snowfall to shoot exteriors of the cabin . In the meantime, Hill had his team lay down rubber mats for the actors to stand on, so that they wouldn’t sink any deeper.

Arrayed on the porch were the actors playing the Sykes family. Costner busied himself with exactly how a canvas shroud covered the dead son, who was lying inside a wooden wagon. “I don’t think you pull this thing down until you want to,” he said to Dale Dickey, the actor who played Mrs. Sykes. “It’s up to you. It’s whatever you feel.”

Costner filmed the actors doing a rehearsal—the parents coming out to see their boy; his brother, explains what had happened—and then gathered the cast around the monitor inside the cabin to watch it back. “I’m going to show you how moments become moments,” Costner told them. As the footage played, he gave notes to Muro. “Let’s not back out, Jimmy,” Costner said to his DP, a playful veteran of Costner projects going back to Field of Dreams. “Whatever we do, I don’t want to swim.”

Costner tends to present like an admiral: someone who is used to being heard and obeyed. But he is remarkable gentle with fellow actors. One by one, Costner took different players aside, talking to them quietly. “Let me see that little reaction to seeing him,” he said to Dickey, about the boy in the cart. “Just that little subtle thing only you can do.” He patted her on the back, then gave a final word of encouragement: “No prisoners.”

Finally, he was ready to shoot a take. “Just hear it all different,” he said, to the assembled cast in the momentary quiet of the set. “Nothing’s different. But it is, every time.”

One of the first things Kevin Costner says in Bull Durham is “I’m too old for this shit.” By this time, Costner was just completing a remarkable early career run during which he’d made Silverado (1985), The Untouchables (1987), and No Way Out (1987)—all hits, all with him in a leading part. He was young and new to the screen, but there was already something about him that was, well, too old for this shit. “Nothing was handed to him,” Shelton told me. “I think you have a reckoning earlier in your life when you grew up without a silver spoon in your mouth: You fight for everything. And I share that with him. Everything’s a fight.”

Costner, who grew up in a conservative California family that moved around a lot because of his father’s work in the utilities business, came late to act. He was an athletically inclined kid, but short and self-conscious about that fact, and the process of new high schools sapped his self-belief. “I lost a lot of confidence in those years,” Costner told me, “and almost lost myself.” He spent his teenage years parroting his parents’ views. “I couldn’t talk out about the war,” he said. Costner’s brother was serving. “I started to write a whole book about my brother in Vietnam,” Costner said. “I mean, I started and stopped.”

In college, at California State University, Fullerton, Costner was not a good student. “I still hadn’t found my own voice,” he said. “Now I’m surrounded by people who knew they wanted to be an architect, who knew what they wanted to be, and I still didn’t know what it was. And I had this realization. I went off and worked fishing boats in the summer, and I had this realization that I need to listen to my own voice and not worry about pleasing my parents. Now, anybody reading this might laugh. It’s like: ‘I didn’t give a shit what my parents thought.’ Well, I did when I was in my teens. I certainly had my own dreams, but I was suppressing them.”

Costner began taking acting lessons and going out for roles. He worked for a time as a stage manager at Raleigh Studios in Hollywood. When he finally became successful, he felt ready for it—like it was an idea that he was already used to. “I didn’t have that young thing of being overly impressed with myself, with my head out the window doing cocaine on the hood of the car,” Costner said. Mostly he was working, trying to catch up. “All the guys that I was competing with had miles of credits—Mel Gibson and Richard Gere and Nicolas Cage and Timothy Hutton and Sean Penn. They were miles ahead of me, had already been making movies for seven, eight years.” Costner said that when he decided to direct Dances With Wolves, after a relatively short time in the business, people told him he was going too fast. But, he said, “that wasn’t fast for me at all. If anything, it was late.”

Still, the industry was skeptical. Some referred to Dances With Wolves as “Kevin’s Gate,” after the infamous Hollywood disaster Heaven’s Gate. “But I didn’t even realize that was happening, that there were these little slings and arrows coming over me just wanting to go do a movie that I promised myself I would do,” Costner said. Even as he continued a long run as a box office star into the ’90s—JFK, The Bodyguard, Tin Cup—Costner was resolute in following his own idiosyncratic impulses. He did 1995’s Waterworld, a big, expensive postapocalyptic film that saw the revival of the Kevin’s Gate epithet and which became notorious for its bloated production and bad vibes, and then 1997’s The Postman—another giant postapocalyptic production, this time produced and directed by Costner —in rapid, masochistic almost succession. Costner sometimes jokes that he should’ve spent these years “doing Bull Durham 3 and 4,” and at the time, he was often miserable.

But, he said, he looked back on these films without regret, and it was in this same spirit that he was embarking on Horizon, another movie that, at a distance, seemed daunting—a challenge Costner couldn’t resist. “I felt time slipping,” he told me. He’d named one of his sons Hayes, after the character in the Horizon script. “He’s now 15”—old enough to be cast in Horizon in a key part. “I thought the window was closing on me being able to be an effective part in that movie,” Costner said. “And so I basically burned my ships.” He went on, trying to make sure I understood: “Like Cortés, we’re fucking here. I’m going to do this. And I mortgaged property. Now do you get it?”

Plus the truth was, despite the steady and lucrative work he had on Yellowstone, Costner needed a job, he said. “We went through COVID, and then I was working and really realized at a couple of points I needed to work a little bit more, for various reasons. Just the instinct of what I would have to do as a quote-unquote provider. I needed to establish a couple of things.”

Costner has made a lot of money in his career, but he’s also spent a lot of money. “I’ve taken some wild swings in life,” he said. As part of a company called Ocean Therapy Solutions, Costner helped develop a technology that separates oil from water; later, during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, he sold several of the devices to BP. “I put $20 million into that,” Costner told me. “I felt like we could handle oil spills differently. I believe in it. I knew I could do it, and it proved out I could do it.” Still, the technology never really caught on. “Did I make a bunch of money? No.” But Costner takes pride in this fact. “I haven’t spent my life trying to make my pile grow bigger,” he said. “I guess I could buy apartments and I could buy McDonald’s and I could buy a bunch of things and just grow, grow, grow, grow,” but instead, he said, he does stuff like mortgage property to make a movie that no one seems to care about besides Kevin Costner.

“That’s the message I want my kids to understand about who I am: that I do what I believe in,” Costner told me. “I have fear like everyone else. I don’t want to be humiliated.” But, he said, his family had a home: They weren’t going to lose it. He mentioned the beachfront property he’d risked for Horizon. “I mean, it’s okay, maybe I lose that. But it’s: Have I lost myself?”

Yellowstone, the show that seemed to return Costner to a prominence in the culture he hadn’t had for some time, premiered in 2018, on the then little known Paramount Network. It became a surprise hit, with episodes that attracted as many as 10 million viewers. On the show, Costner plays John Dutton III, a proud and dangerous ranch owner whose desire to hold on to his property, and to the way of life it represents, leads to a series of escalating and tragic conflicts inside his family and out. Yellowstone was soapy but also showed a world, grounded in the modern West, that hadn’t been seen much on television before. And in Costner, the show finds its perfect match—horses, old-fashioned values, stoicism, all the stuff that Costner projects now just by showing up—even as it played him slightly against type, as a Godfather figure complicit in violence and death in the name of keeping what’s his. As the years passed, the show only grew bigger, spawning multiple spin-offs and elaborate merch, and Costner again found himself at the center of a giant. Until, suddenly, he wasn’t.

It was only early last year that word began to trickle out about a potential rift between Costner and Yellowstone’s cocreator Taylor Sheridan, and the show’s producers, Paramount and 101 Studios. Costner, who has been known to clash with directors and studio heads, has made no secret of his stubbornness in the past, and as the press began to avidly cover the situation, there were whispers about unreasonable financial and schedule-related demands, bids for creative control. Until now, Costner has made a point of not refuting those claims publicly in any kind of detail. “That’s kind of my Western ethic,” he said. “I’ve been quiet about the whole thing and I’ve taken a beating out there. My castmates are confused. The crew was confused.”