Fred G. Sanford was a junk man, and Redd Foxx was the master of trash talk. Sanford and Son turns 50.

Sanford and Son, the first mainstream, primetime sitcom in television history with an almost-all Black cast, debuted on NBC on Jan. 14, 1972. Created by Norman Lear, and starring legendary “blue” comedian Redd Foxx as an African American bigot, it was seen as a direct answer to CBS’ All in the Family. But the Bunker family series was a social satire which took its laughs seriously. The Sanfords presented pure comedy, any lessons it taught were intentionally coincidental. The most controversial part of the show, when it first aired, was its lead actor.

Foxx was already an underground comedy legend when Cleavon Little, best known for his role as Sheriff Bart in Mel Brooks’ Blazing Saddles, suggested him for the lead in the mid-season replacement. Little wasn’t available, but worked with Foxx on Ossie Davis’s 1970 neo-noir film Cotton Comes to Harlem. Before Foxx played the junk dealer stuck with the bale of genuine Mississippi cotton, he was known as the “King of the Party Records.”

In a time of repressed standup, Foxx worked notoriously “blue.” He agreed to clean up his act for television, but consistently fought to keep Sanford and Son authentically funny. Born John Elroy Sanford, raised on Chicago’s South Side, and relocated to Harlem, he was known for keeping it real. In The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965), Malcolm X called “’Chicago Red,’ the funniest dishwasher on this earth.” Foxx started out as a singer, and ate half a bar of soap to get out of the draft during World War II. He got heart palpitations during the physical. But not “the big one, Elizabeth,” it was only a warm-up to one of the show’s running gags, which Foxx stole from his own mother.

“I’m 65. People say I look 55. I feel 45. I’d settle for 35 and you make me feel 25.”

The character Fred G. Sanford is a 65-year-old widower on Sanford and Son. Foxx was 49 when the series began, but personalized the part and the show. Fred Sanford was named after Foxx’s brother, who died five years earlier. Lamont Sanford, played by Demond Wilson on the series, was named after Lamont Ousley, who was in a washtub band with Redd when they were both teenagers.

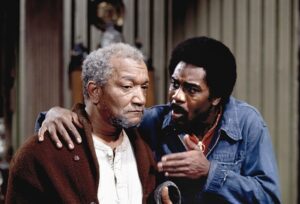

While published reports contradict whether Wilson and Foxx met in Las Vegas or on set for the first time, their chemistry was instantaneous, and their timing was expert. There is a palpably genuine affection between the two actors. Wilson began acting after serving in the Army’s 4th Infantry Division in Vietnam from 1966 to 1968, when he was wounded and discharged as a decorated veteran. He began in live theater, and was featured in Broadway and Off Broadway shows. He acted in the films The Dealing (1970) The Organization (1971), and series like Mission: Impossible. Producer Bud Yorkin took notice when Wilson and Cleavon Little played burglars on All in the Family in 1971.

Foxx fought to cast school friend, and fellow blue stand-up, LaWanda Page, as Sanford’s Bible-thumping, finger-wagging sister-in-law, Esther Anderson. “Watch it, sucker,” Page’s burlesque dance title was “the Bronze Goddess of Fire,” and she could light cigarettes with her fingertips. Foxx also made sure the comic Slappy White was featured as a guest star. They’d both got their first break opening for blues singer Dinah Washington.

The rest of the cast was split between Fred’s friends Skillet (Ernest Mayhand), Leroy (Leroy Daniels), and Bubba Bexley (Don Bexley), and Lamont’s friend Rollo (Nathaniel Taylor). Grady Wilson, played by Whitman Mayo, went from the lovable wino, “Shady” Grady, to Lamont’s guardian when Foxx called in sick.

“Junk runs in the family. My granddad was a junkman in St. Louis and so was my uncle.”

All in the Family was based on the BBC1 television sitcom Till Death Do Us Part. Sanford in Son was based on the British sitcom Steptoe and Son, which starred Wilfrid Brambell (A Hard Day’s Night) and Harry H. Corbett as a father and son in the “rag and bone” business on Oil Drum Lane. Producers Lear and Yorkin relocated them to 9114 South Central, in the Watts section of Los Angeles.

Besides retooling many of the original series story ideas, many Sanford and Son plots are standard TV fare, like get-rich-quick schemes which go back to The Honeymooners. Grittier plot lines, like inflating collectible prices or feeding local cops some potent homegrown edibles, gave way to silly clichés like earthquakes, racehorses, and getting hypnotized to stop watching too much TV, in the later seasons.

Fred’s jokes were frequently cruel, but Foxx kept the character lovable. He was nominated for an Emmy. which he lost to Carroll O’Connor, and would go on to get two more nominations. Fred Sanford made people laugh, but rarely challenged the audience.

Like All in The Family, Sanford and Son got laughs from the generation gap and the cultural divide. “Watts Side Story,” from season 2 in 1973, introduces Mrs. Providencia Fuentes (Alma Beltran), a Puerto Rican mother, and her grown children Maria (Migdia Chinea), and Julio (Gregory Sierra), who would become a series regular. Both Mrs. Fuentes and Fred do not approve of interracial romance, and flip out when Maria and Lamont date. This is not a problem for the younger characters.

“If you see the handwriting on the wall, you’re in the toilet.”

Both of Lear’s series highlight humor through overt prejudice. But while All in the Family had a political purpose, bigotry was merely a joke device on Sanford and Son. The humor was based on the broadest of generalizations. When Fred has to get his teeth fixed, in the episode “In Tooth or Consequences,” he’d rather go to white dentist than a Black one. An Asian character played by Pat Morita, who Foxx mentored in comedy clubs, is named “Aw Choo.” Fred’s favorite endearing term for his son is “big dummy.” The n-bomb is first detonated in the third episode, “Here Comes the Bride, There Goes the Bride,” with a teleplay by Aaron Ruben.

Foxx fought with NBC and the series’ producers to include this kind of humor. In spite of his edgy delivery, Foxx was the first African American comic to headline Las Vegas when he played the Aladdin Hotel in 1966. He proved himself clean enough for TV after appearing on The Tonight Show, The Joey Bishop Show, and The Flip Wilson Show. But his reputation preceded him. When Quincy Jones submitted “The Streetbeater” as the theme song, he did not believe any network could “put Redd Foxx on national TV.”

The dirty standup also brought along his biggest successors. Richard Pryor wrote two episodes with comedian Paul Mooney during the show’s second season: “The Dowry,” which was episode 3, and episode 11 “Sanford and Son and Sister Makes Three.” Pryor had played Foxx’s Los Angeles comedy club, and frequently partnered with Mooney, who also wrote for the film Richard Pryor: Live on the Sunset Strip, and the much-too-short-lived TV series The Richard Pryor Show. As a stand-up known as the “Godfather of Modern Black Comedy,” Mooney was part of the post-Lenny Bruce wave of boundary-pushing comics like Dick Gregory, George Carlin, and Pryor. He would go on to write for In Living Color, The Chappelle Show, and play Junebug in Spike Lee’s 2000 film Bamboozled.

In spite of its commitment to pure comedy, Sanford and Son still found ways to lacerate the times with cutting edge social commentary. The series took on racial profiling in “Fred Sanford, Legal Eagle.” With a teleplay by Gene Farmer from a story he wrote with Paul Mooney, the season 3 episode ran on Jan. 11, 1974. In the episode, Lamont decides to fight a traffic ticket after part-time lawyer/full-time tailor Sonny Cochran (Antonio Fargas) advises he “throw himself on the mercy of the court.” Just as Lamont is ready to represent himself, Fred mounts his own defense. “What problem do you have with Black drivers,” Sanford demands to know, seeing only African Americans on trial in the courtroom. “Why don’t you arrest some white drivers?”

“We’re gonna do like the Red Sea and split.”

Foxx wanted to know the same thing about Black writers on his show. Sanford and Son had enough white producers to cast a Tarzan film, but white writers continued to dominate the scripts. Between this and a substandard contract, considering he saved NBC in the ratings, Foxx walked off the series during season three. Sanford And Son was an instant hit because of Foxx, and he wanted 25% ownership. Tandem Productions sued him for $10 million.The best thing to come out of it was the season 5 episode “Steinberg and Son,” which spoofed the show, the series which created it, and the lawsuit itself.

After season six ended in March of 1977, Foxx defected to ABC to host The Redd Foxx Comedy Hour. The variety show was canceled after a month. He came back to star on NBC’s retooled versions of the show, Sanford Arms, which premiered on Sept. 16, 1977, and its sequel series Sanford. Neither lasted long. Foxx kept the 1951 Ford F1 truck which appears in every episode.

After the series ended, Wilson took the lead in the CBS sitcom Baby, I’m Back, which ran for 13 episodes. He played Oscar Madison to Ron Glass’ Felix Ungar in ABC’s The New Odd Couple. He also starred in BET’s Demond Wilson and Company, and the TV series Girlfriends. Wilson’s last film appearance was in the 2000 prison comedy Hammerlock. His last stage role was in a 2011 touring production of the faith-based play The Measure of a Man. In 1995, Wilson formed Restoration House of America, which provides rehabilitation services for former prison inmates.. He has written eleven children’s stories, and several books, including Second Banana: The Bitter Sweet Memoirs of the Sanford and Son Years.

In 1989, Eddie Murphy cast Foxx as craps dealer Bennie Wilson in the film Harlem Nights. The film also starred Pryor and Della Reese, who was cast as Foxx’s co-star in his comeback sitcom, The Royal Family. The working title for the series was “Chest Pains.” Foxx suffered a heart attack on Oct. 11, 1991, during rehearsals for the show. His fellow cast members initially thought he was joking. Foxx died later that night at the hospital.

After 50 years, Sanford and Son continues to inspire comedy and invite controversy. Its groundbreaking assault on social sensibilities continues to rabbit punch modern sensitivities, right in the funny bone. The original run only lasted six seasons, but neither Redd Foxx nor Sanford and Son can ever be canceled.