Death, in the Final Destination franchise, has a design—and an OCD-like preoccupation with executing it in precise order. The six-movie (so far) series started with 2000’s Final Destination and continues after a nearly 14-year break this weekend with Final Destination: Bloodlines. All of its movies do away with its characters in the methodical fashion of a slasher movie, except without the actual slasher. The villain occupies no corporeal vessel; instead it’s an unseen force referred to by its characters as “Death” and has Freddy Krueger’s flair for devising interest-specific demises. (At least those high school seniors that got burned to death in the tanning bed died doing what they loved.) In these movies, the only thing Death loves more than combining water and electricity is foreshadowing in the form of things like in-universe music cues, breezes, and giving characters teasing hallucinations of what’s to come. (A close third: poles going through the back of people’s heads and out of their mouths.) Death’s goal is to settle the score—those who manage to evade it are condemned to face it, usually sooner rather than later.

The temporary evasion comes via visionaries, spontaneously psychic protagonists who foresee a major disaster, snap back to reality, realize what’s happening, and hightail it to safety, taking a few confused hangers-on with them. Said disasters have included an airplane accident, a highway pile-up, a race-track crash, and a bridge collapse. The survivors of these tragedies then die in the order that occurred in the original vision. The Final Destination franchise has a practically religious devotion to the concept of fate, and the ritualistic samey-ness of all of the sequels, save Bloodlines, carries with it the kind of comforting familiarity of a competition reality show that follows the same format each week, insofar as depictions of disemboweled teenagers can be comforting.

The devilish appeal of this premise has been proven repeatedly. The first five Final Destination movies have earned an international box-office gross of (you can’t make this up) $666 million. The novelty of the original film’s premise has been upheld by the subsequent films’ explorations of the potential dangers lurking in the quotidian: a car wash, a LASIK-performing doctor’s office, and a Home Depot–style big box store were among the death traps. These set pieces are the source of the films’ ingenuity and what must keep people coming back to watch them over again. In a bigger-picture kind of way, the Final Destination movies impose logic on death to help make sense of something that’s often senseless. That’s a goal of a lot of horror movies, or media about death in general, but there is an uncommon organizational formality in the Final Destination movies, a tangible, even relatable, striving to delay death.

The original has remained the best of the series’ entries overall, quite simply because it set the template. Very little elaboration occurred over the course of the next four movies. When there have been attempts to expand on the mythology, it’s gone off the rails like, well, a rollercoaster in a Final Destination movie (the third one, to be precise). In Final Destination 2, the survivors of that huge highway pile-up have the convoluted realization that they’d previously been spared death as a result of the mass deaths in the first movie (via plane). Final Destination 5 introduces the idea that those whose time is up can avoid death by killing someone else and taking their time, a karmic curveball that defies the ideology of the series for the sake of a jarring climax. There are plenty of lapses in logic along the way. Why does Death sometimes off someone quickly and directly (with, for example, a piece of metal sliced right through the head), but at other times set a bunch of potential traps that then fire off in Rube Goldberg–ian succession? Why does it seem to back off when people think they’ve escaped the curse only to inevitably come raging back when the narrative needs a little kick? What is even the point of the spontaneous ESP that allows characters to escape Death if it’s only going to come for them within the 90 or so minutes it takes for the movie to unspool? If Death is so powerful, shouldn’t it be able to prevent those visions?

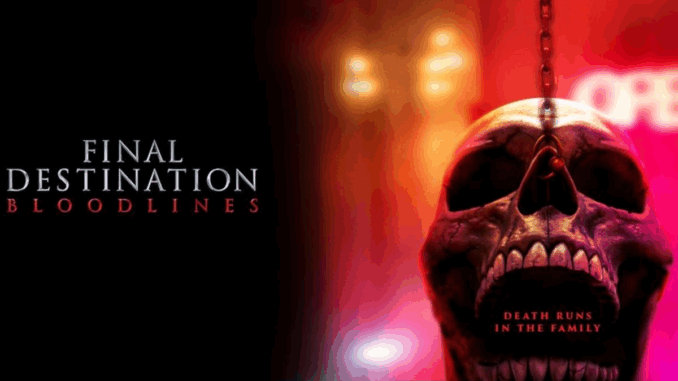

Final Destination: Bloodlines is different enough from the rest of the sequels to justify its own existence. It’s most certainly the best film in the series since the original (it’s the first Final Destination movie to be “certified fresh” on Rotten Tomatoes), with the most naturalistic acting and the most pleasing aesthetics. (The cool temperature of its picture is classy as opposed to the movies’ usual garishness.) It begins with a riff: Again we’re treated to a spectacular disaster (in a restaurant 500 feet in the air with a glass floor à la the Loupe Lounge in Seattle’s Space Needle), but this time it’s not a premonition—it’s a dream. Stefani Reyes (Kaitlyn Santa Juana) has been plagued by this dream (one that she’s not in, mind you, that she just watches like a movie) for two months and, as a result of lost sleep, is on academic probation at college. Her desperation leads her to the discovery that her dream was the vision of her grandmother Iris (Gabrielle Rose) some 50 years before. After Iris saved everyone’s life, Death visited not just the surviving diners but their families as well, because, as Iris explains, “Death doesn’t like it when you fuck with his plans.” Death, ever obsessed with order, kills members of families from oldest to youngest. Her family has gone untouched for so long because Iris has spent decades holed up in a bunker, like Laurie Strode when we meet her in the 2018 Halloween reboot. Iris then, naturally, dies, because she has to in order for us to see all the fun set pieces.

Said pieces include death via lawnmower, garbage-truck compactor, and MRI. As in the rest of the series, the underlying inevitability to the proceedings is at odds with the suspense we expect from horror movies. The person whose time is up is almost always announced before they go, so it’s not a matter of who but of how. There are a few breath-snatching moments here and there (Stefani stuck in a submerged van as a result of a broken seat belt is a particularly well-staged scene), but Bloodlines generally strikes a balance between gruesome and funny as it sprints along. There are knowing winks sprinkled throughout referencing other entries in the franchise, like a truck carrying logs (the same type that caused the pile-up in 2), rods protruding through a skull tattoo on one character’s abdomen in the style of 5’s poster, and a reference to the name of Ali Larter’s character from the first two movies, Clear Rivers. Bloodlines is a movie with awareness of the franchise’s fervent fan base (more than 24,000 people follow r/FinalDestination), and instead of regurgitating—which it totally could have done, all the way to the bank—it seeks to expand the mythology to a degree that no previous sequel has done, and with a much greater deftness. Some bits of world-building may feel a bit arbitrary (new rule: If you die but are brought back to life, the curse is broken!), but the bloodline plot facilitates some poignancy in a franchise whose characters have largely seemed blasé about all the death around them.

Most affecting is the lingering presence of Tony Todd, who is perhaps best known for his titular role in the Candyman movies. Todd has also played mortician William Bludworth in most of the Final Destination movies. He died last November, so Bloodlines marks his final film role. As usual, his Bludworth serves as a de facto narrator, spouting such pearls of wisdom to the confused kids as “If you fuck with death and lose, things can get very messy.” But he also muses about life and death more generally, and according to producer Craig Perry, most of these lines were impromptu and directed at fans. Before exiting the screen for good, a gaunt Todd tells us, “I’m retiring … I intend to enjoy the time I have left, and I suggest you do the same. Life is precious. Enjoy every single second. You never know when … Good luck.” A Final Destination movie that takes death seriously and is moving in the process? Who could have seen it coming?