Bridgerton’s big question: was Queen Charlotte really our first black royal?

The writer of the raunchy romances which inspired the Netflix show claims she was. What’s the evidence?

It’s starting to become a habit. Netflix has found itself caught in another controversy over historical accuracy, this time over its romping Regency drama, Bridgerton.

At first blush, it seems the bodice-busting show has plumped for colour blind casting. It’s an established practice in theatre – and is starting to become more popular in films, such as Armando Iannucci’s recent Dickens adaptation, The Personal History of David Copperfield.

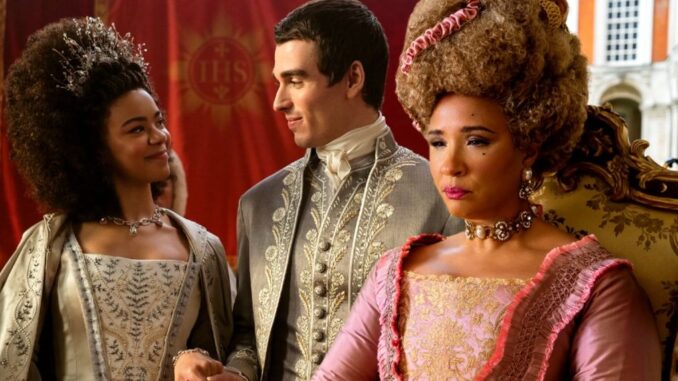

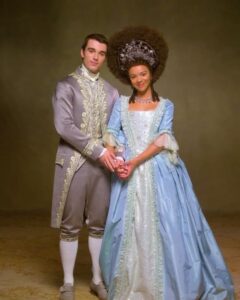

But the casting of black British actress Golda Rosheuvel, 49, as Queen Charlotte appears to have been a deliberate nod to a tenuous historical theory – that George III’s consort was Britain’s first black queen. This is especially telling as Queen Charlotte is the most prominent real-life figure in the show; the duelling families around which the drama swirls are fictitious.

“Many historians believe she had some African background,” said Julia Quinn, the American author whose series of romance novels inspired the show. “It’s a highly debated point and we can’t DNA test her so I don’t think there’ll be a definitive answer. What if she used that position to bring other people of colour to positions of power? What would society have looked like?”

That there’s debate about Queen Charlotte’s ancestry will surprise those whose main encounter with this somewhat forgotten figure was Helen Mirren’s warm performance opposite Nigel Hawthorne in the 1994’s The Madness of King George.

Nonetheless, the idea that Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz was black has proved tenacious. It was brought to widespread attention by the historian Mario de Valdes y Cocom; his argument rests partly on historical portraits, including Sir Allan Ramsay’s famous depiction, which show her with stereotypically African features.

But the critic and historian Lisa Hilton has pointed out that this portrait is far from conclusive.

“The Ramsay portrait shows a reddish-haired woman with blue-grey eyes, a large nose, heavy chin and full lips,” she says. “Such features were considered unattractive according to the standards of beauty of the age and since royal portraiture is not known for its harsh realism, these features may certainly have been softened by other painters, without any necessary disguising of the colour of Charlotte’s skin.”

She also notes: “None of the other considerable body of portraiture, for example works by Zoffany and Gainsborough, is suggestive of ‘mulatto’ blood. It seems unlikely that in an age when cartoonists depicted the royal family in the most scurrilous of situations (having sex, defecating), there should be no other visual reference to what, after all, would have been a fairly startling feature.”

Cocom untangles a cat’s cradle of bloodlines to argue for Charlotte’s African heritage. Though the queen was German, he claims she was directly descended from a black branch of the Portugese royal family. This ‘black’ inheritance can be traced back to the 13-century ruler Alfonso III and his lover Madragana, who was a Moor and thus – by Cocom’s reckoning – black.

“Moor”, though, was not synonymous with African descent. In fact, argues Hilton, it was “a general term for the inhabitants of the Moorish empire in North Africa and Spain. Moreover, the 500 years between Mandragana and Charlotte would suggest any African bloodline would have been significantly diluted.”

Cocom marshalls two further pieces of evidence. The first is that Queen Charlotte’s physician, Baron Stockmar, described her at birth as having “a true mulatto face”. But Stockmar’s eyewitness statement becomes less convincing when it’s recalled that he was born in 1787 – 43 years after Queen Charlotte was born in May 1744.

Second, Cocom cites a poem composed for her wedding to George III and his coronation:

Descended from the warlike Vandal race,She still preserves that title in her face.Tho’ shone their triumphs o’er Numidia’s plain,And Andalusian fields their name retain;They but subdued the southern world with arms,She conquers still with her triumphant charms,O! born for rule, — to whose victorious browThe greatest monarch of the north must bow.

The Vandals were a conquering tribe, though; their presence on “Numidia’s plain” speaks to itchy-footed expansionism, not native African descent. Besides, the scurrilous literary atmosphere of court – enjoyably captured in Bridgerton – would have made the warlike Vandals a canny allusion for a poet looking to poke fun at the new queen’s German heritage. Despite this, the poem is cited in 100greatblackbritons.com as evidence for Charlotte’s inclusion on that list.

Queen Charlotte – whatever her skin colour – has had a bruising ride in the historical record. For the historian John H Plumb she was “plain and undesirable”. And she’s summoned memorably in the opening of Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities: “There was a king with a large jaw, and a queen with a plain face, on the throne of England.” One courtier even purred of the elderly queen: “Her Majesty’s ugliness has quite faded.”

Yet her legacy shouldn’t rest on her physical appearance. Though she found herself queen of a foreign country aged only 17, she became a patron of the arts, founding Kew Gardens and possibly commissioning Mozart. She also bore 15 children – 13 of whom survived into adulthood.

Perhaps, then, Golda Rosheuvel simply best embodied this formidable woman? Quinn said she had aspired to “historical plausibility”, not accuracy, in her Bridgerton novels; and Golda Rosheuvel has a dreadnought stateliness entirely suited to the role.

In fact, Queen Charlotte is celebrated as a hero in Charlotte, North Carolina. There are two statues to her in the city, including one in which she has notably black features. She is seen as an inspirational figure, despite her husband declaring war on America in 1775.

“We think [she] speaks to us on lots of levels,” Cheryl Palmer, director of education at the Mint museum, has said. “As a woman, an immigrant, a person who may have had African forebears, botanist, a queen who opposed slavery – she speaks to Americans, especially in a city in the south like Charlotte that is trying to redefine itself.”

There’s an element of nudge-nudge camaraderie in the city’s embrace of Queen Charlotte. “I believe African-American Charlotteans have always been proud of Queen Charlotte’s heritage and acknowledge it with a smile and a wink,” said Eula Watt, wife of first African-Americans in the House of Representatives. “Many of us are now enjoying a bit of ‘I told you so’, now that the story is out.”

She may not have been Britain’s first black queen, then. But as the city which bears her name proves, Queen Charlotte has long been overdue her recognition.