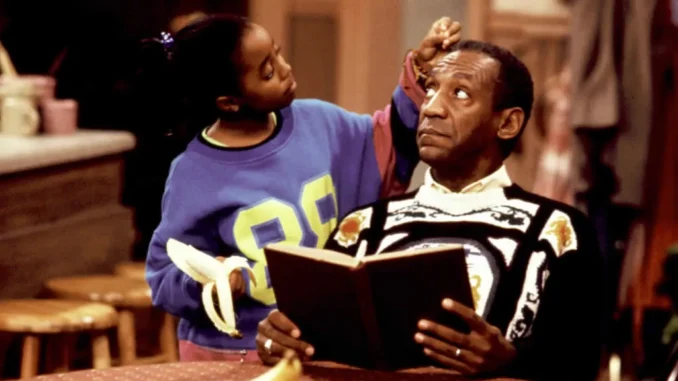

Thirty years ago this September, NBC aired the pilot for a new situation comedy on eight o’clock on Thursday night. At the time, there wasn’t a single sitcom in the Nielsen top twenty, and many in the TV industry had declared the format “dead.” In an upfront presentation for advertisers, network president Brandon Tartikoff predicted tepidly that the show would finish second in the time slot to “Magnum P.I.” on CBS; in an advance review critic David Bianculli pleaded with NBC not to “dump it” prematurely. And when viewers tuned into the pilot, they weren’t treated to the usual drum-roll introductions to the show’s character and premise. All they saw was a typical day in the life of an American family: the kids and parents bickering over what kind of music to listen to over breakfast, the teenage daughter getting ready to go out on a date, the dad having a stern talk with his son about a dismal report card.

Yet “The Cosby Show” didn’t just win the time slot that night. It went on to dominate TV for the rest of the eighties, topping the ratings for five straight years, reviving NBC and pulling all the sitcoms that aired after it into the Nielsen top ten. In the sentimental glow with which it is now remembered, it’s easy to forget how astonishing it was that a comedy about black people could have that kind of success, or to assume that it did so only because the Huxtables were, as New York Magazine once sneered, “little more than ‘Leave it to Beaver’ in blackface.” As unfair as that verdict was at the time, it seems even more ludicrous now, in light of the failure of any show in the three decades since to come close to matching the impact that “The Cosby Show” had on how African-Americans are perceived and how they perceive themselves.

The premiere next week of “Black-ish,” a new ABC sitcom about a black family, provides a reminder of just how quietly radical “The Cosby Show” was. Like Cliff and Claire Huxtable, Andre and Rainbow Johnson (played by Anthony Anderson and Tracey Ellis Ross, the daughter of Diana Ross) are successful black professionals: an advertising executive and a doctor, raising their three children in an affluent mixed neighborhood. But in every other way, “Black-ish” is more of a throwback to shows like “The Jeffersons” and “Fresh Prince of Bel Air,” where the humor is always directly or indirectly about race, and rarely is it subtle. Born in “the hood,” Andre is obsessed with “keeping it real” at work and at home—a loss-of-identity crisis that leads him to do clownishly implausible things like include a ghetto riot in an ad for the L.A. tourist board, dress his son in tribal garb for “an African Rights of Passage” ceremony and bait his biracial wife for not being truly black (hence “black-ish”).

For Cosby, keeping it real meant something very different. While his show was still in development, Cosby reached out to Dr. Alvin Poussaint, a Harvard psychiatrist whose specialty is minority children, and asked him to read scripts to make sure they reflected genuine child psychology and family dynamics. Sensing that Poussaint was going easy on laugh lines, Cosby told him to be even tougher: “Your job is to check reality,” he said. “My job is to make it funny.” Cosby stuck by his guns when network boss Tartikoff criticized the thin plot lines of the early episodes. (Rudy’s pet goldfish dies; Theo gets cut from the football team; Denise botches the sewing of a knock-off designer shirt.) Shooting the second season premier, Cosby threatened to walk off the set when the network sought to appease advertisers by removing an “Abolish Apartheid” sign from Theo’s bedroom door. “There may be two sides to apartheid in Archie Bunker’s house,” he declared. “But it’s impossible that the Huxtables would be on any side but one.”

Affectionate with fellow cast members, Cosby could be hell on writers, making fun of their contrived jokes and riffing on their carefully-crafted dialogue, like the jazz musician he once wanted to be. Yet today, even some of the most bruised survivors credit him with ushering in a down-to-earth style of comedy that would help pave the way for shows like “Seinfeld” and “Home Improvement,” and later “Curb Your Enthusiasm” and “Portlandia,” where actors are encouraged to improvise. Combined with Cosby’s insistence on sticking to universal themes of family life, that naturalism allowed his show to go in new and unpredictable directions every week. Some episodes could have nothing to do with race; others could revolve around jazz, or black art, or remembering the March on Washington. Watching the “Black-ish” pilot, with its one-note identity fetish and over-scripted laugh lines—“Not really black!” Rainbow retorts, “Tell that to my hair and my ass!”—you wonder how the show will avoid repeating itself.

By the end of the first episode, however, it’s clear that “Black-ish” also aspires to express the yearning of African-Americans not to be totally defined by skin color. Andre is disappointed when he is promoted to vice-president of his firm’s “urban division” because he wanted to be “the first vice-president who just happened to be black.” And when he eventually supports his son’s decision to play field hockey rather than basketball and agrees to throw him a hip-hop bar mitzvah, even though the family isn’t Jewish, he tells the audience: “I didn’t feel urban, I just felt like a dad who was willing to do whatever he could to support his family.” Given time, perhaps “Black-ish” will find its way to the higher ground that Bill Cosby miraculously seized from day one and occupied for almost a decade thirty years go. You can almost hear Cliff Huxtable in the voice of Andre’s father, played by an underutilized Laurence Fishburne, when his son asks how he kept it real.

“I didn’t keep it real,” Pops replies. “I kept it honest.”

Mark Whitaker is the author of Cosby: His Life and Times, the biography of Bill Cosby out this week, and the critically acclaimed memoir, My Long Trip Home. The former managing editor of CNN Worldwide, he was previously the Washington bureau chief for NBC News and a reporter and editor at Newsweek, where he rose to become the first African-American leader of a national newsweekly.