The Nanny’s Loud Body

Late in the series run of CBS’s The Nanny, the show’s aesthetics of excess finally confront their final frontier: fatness. Thick thighs befall the titular nanny, Fran Fine, a wisecracking and trashy-fabulous woman from Queens. It’s unexpected. She’s finally about to seal the deal with the stern and respectable father of her charges, whose heart she’s melted with her wacky antics. But a bad reaction to an allergy shot makes her balloon in size, still stuck inside her skintight dress. “Oh Mr. Sheffield,” she moans, “you’re never going to find me attractive again!” Ever gallant, Mr. Sheffield replies through a grimace, “Miss Fine, don’t you be ridiculous! There’s two—three—six times as much of you to love!” This claim isn’t convincing; Fran mutters to the doctor, “Kill me, please.”

On The Nanny, fat is the worst possible thing you can be, and it can happen to you at any moment. As it turns out, Fran’s swelling has resulted from a counterreaction to something she ate: a bowl of her mother’s diet soup, which contains vegetables, and, if she’s honest, a little bit of tortellini—just for flavor. In this punchline, fatness is revealed to be an inherited sin, transferred from mother to daughter for maximum comedic disaster. Only when Fran is “deflated” can the romantic plot of the show recommence.

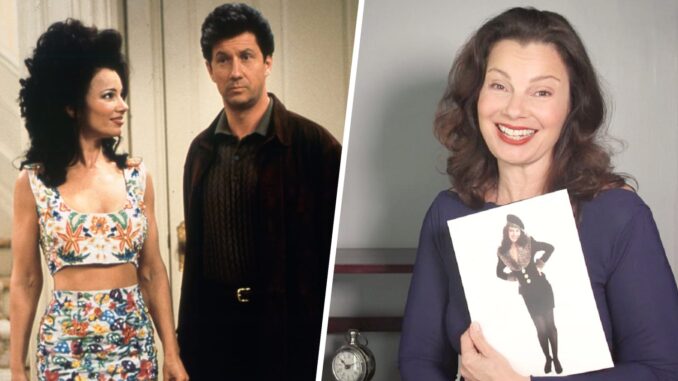

The sitcom made a frequent habit of cruel fat jokes and plotlines like this one. It’s one of a long series of shows that have used the fat suit device, from Friends to more recent fare like New Girl and Mad Men. But in The Nanny, the embrace of fat jokes is strange. It’s weird for a show that embraces so many other kinds of bigness: loud voices with exaggerated Queens accents; broad, slapstick comedy; bright, over-the-top outfits. The incongruous fear of fatness ultimately reveals what kinds of excess seemed possible for women on television in the 1990s. Revisiting its preoccupation with fat jokes demonstrates the (limited) extent to which TV has moved on. However, The Nanny has a limited place in our collective television memory, making appearances on niche social media accounts rather than a big streaming platform. As a result, its impact on a longer comedy tradition is in question. How do we remember a show that expanded the limits of what was lovable—but still placed fat people firmly outside the lines?

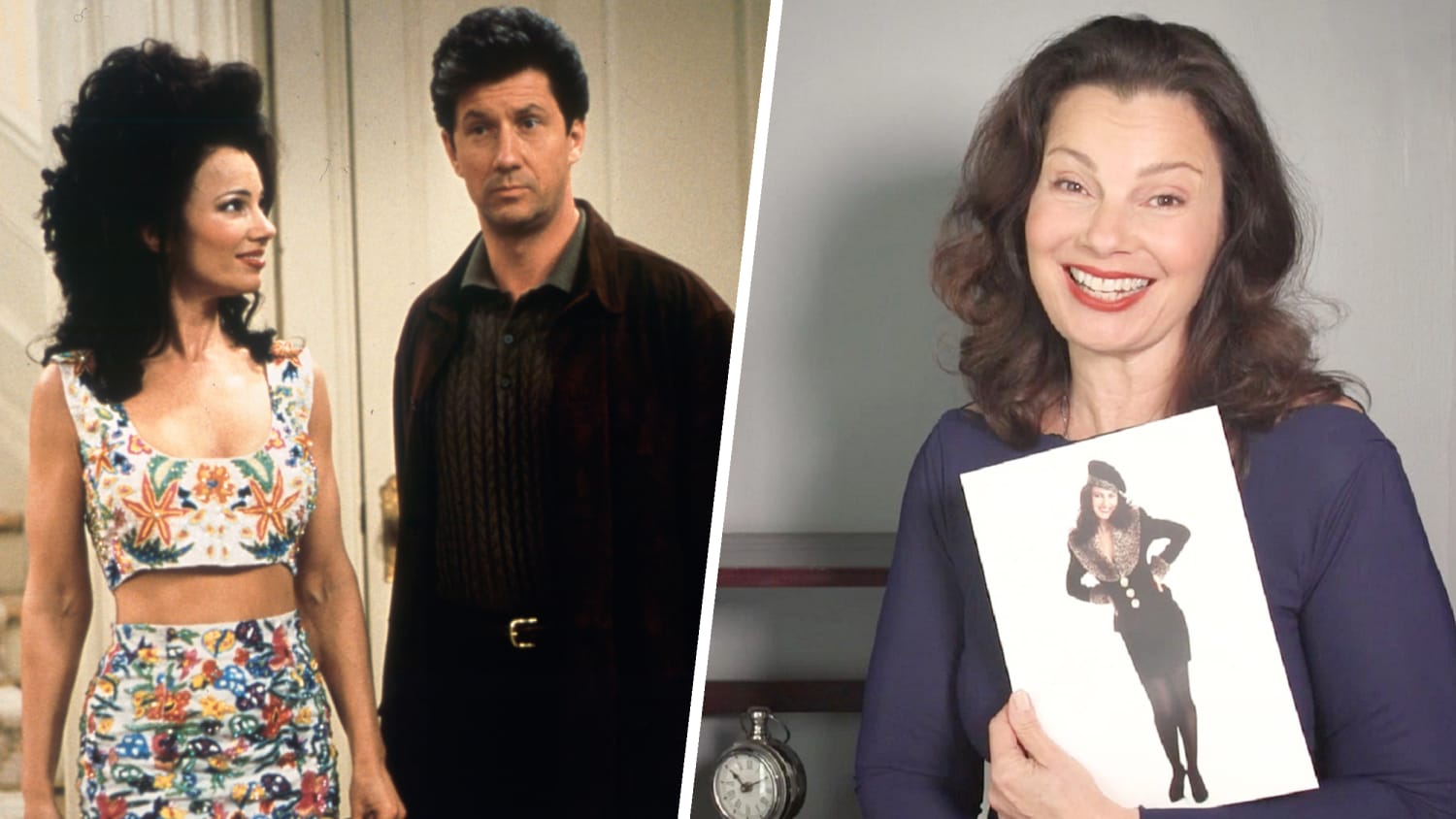

In its aesthetics and its humor, The Nanny evinces an admiration for excess that extends right up to the possibility of having an excessive body. It ends there absolutely, obsessively prodding that boundary. Outside allergic incidents, Fran is known for her big hair and her tiny waist, and she is convinced that in the combination lies her only chance of getting somewhere in life. The show’s representation of fatness as threatening is at odds with its central thesis: that tackiness and loudness are primary source of charisma, connection, and power. Fran’s unpretentious street-smarts and Yiddish-heavy vocabulary are the qualities that endear her to the Sheffield family and ultimately secure her place within it.

But she perceives these traits to be acceptable precisely because she is beautiful, and most of all thin. And, in the logic of the show, she’s probably not wrong. The Nanny derives comedy from the revolting possibility that Fran might turn into her mother, who is constantly eating and—quelle horreur—a size twelve. Sylvia Fine turns up near daily at the Sheffield mansion to munch on cream puffs and terrorize the WASPy Sheffields by reminding them that the vivacious nanny they love may someday place her appetite for carbs over her appetite for Loehmann’s sales on teeny-tiny crop tops.

Fran is at frequents pains to assure Mr. Sheffield that this will not happen. She seems to know that her beauty is a condition of acceptance—a kind of apology for her aesthetic and temperamental bigness, and for her Jewishness. Probably this understanding arose from star and executive producer Fran Drescher’s real experiences in Hollywood, but she reproduces the expectation more or less uncritically. In this way, she follows in the footsteps of one of her comedy forebears, and one of the only big stars of the ‘80s not to cameo on her show: Joan Rivers.

Rivers, an unarguable pioneer for women in comedy, was famous for admitting — or insisting — that “looks matter.” She was uncharitable to women who didn’t take this mandate seriously. In a late interview on the Howard Stern show in 2014, she brought up Lena Dunham’s body unprompted. She pretended to be critical for health reasons, mentioning the specter of diabetes, before coming eloquently to the point: “But don’t make yourself, physically—don’t let them laugh at you physically.”

For Rivers, the physical body, specifically the fat body, was the point at which you can’t control whether people are laughing at or with you. TV critic Emily Nussbaum writes of the quote that Dunham “was violating the rules that Rivers built her life