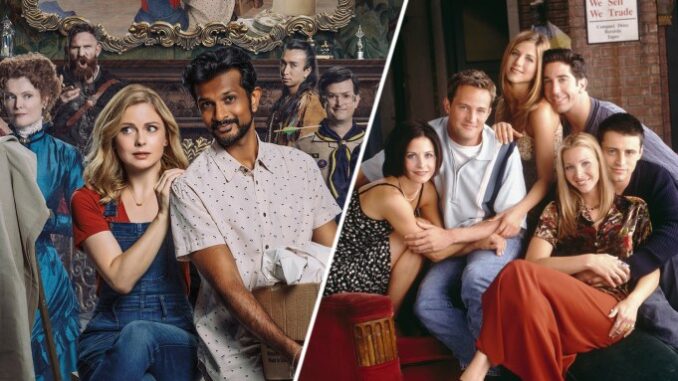

The Spectral Echo: How Central Perk's Comfort Inspired Button House's Chaos

At first glance, the BBC comedy Ghosts and the iconic American sitcom Friends seem to occupy entirely different universes. One, a whimsical tale of a young couple inheriting a crumbling stately home teeming with the spectral residents of centuries past; the other, a foundational sitcom chronicling the urban misadventures and coffee shop confessions of six twenty-somethings in New York City. Yet, as a BBC producer might explain, the invisible threads of creative inspiration are often spun from the most unexpected spools. The secret ingredient that transformed Button House from a mere haunted house into a beloved home for millions was, surprisingly, the palpable, endearing chemistry of Monica, Chandler, Phoebe, Joey, Rachel, and Ross.

The enduring success of Friends wasn't solely predicated on its sharp wit or relatable millennial angst. Its true magic lay in the meticulous crafting of its ensemble. Viewers didn't tune in merely for the jokes; they tuned in for the comfort of familiarity, the reassuring hum of a surrogate family navigating life's absurdities together. The characters were distinct, flawed, and utterly devoted to one another. Their apartments, Central Perk, even Monica's meticulously organized kitchen, were not just sets but crucibles for their relationships. The humor often sprang not from grand plotlines, but from the everyday friction and affection of people who knew each other inside out, their quirks amplifying each other in a symphony of lived-in comedy. It was, at its heart, a show about "found family."

Now, imagine the challenge of creating a comedy where the "family" includes a Georgian noblewoman, a World War II captain, a romantic poet from the Romantic era, a caveman, and a perpetually pantsless Edwardian baron, all sharing a living space with a thoroughly modern, living couple. The potential pitfalls are numerous: it could be too niche, too reliant on historical gags, too fantastical to ground. This is where the Friends paradigm offered a guiding light, a conceptual north star for the creators of Ghosts. The producer's epiphany would likely have been this: if Friends could make a group of disparate individuals so utterly compelling simply by virtue of their shared lives and interwoven dynamics, why couldn't the same principle apply to a group of dead individuals?

The Ghosts team understood that the key wasn't the haunting itself, but the cohabitation. The focus shifted from the "how" of their spectral existence to the "who" of their personalities and the "what" of their interactions. Each ghost, despite their era and manner of death, was given a distinct, often exaggerated, personality designed to bounce off the others and, crucially, off the living protagonists, Alison and Mike. The humor, like in Friends, wasn't just in the punchlines; it was in the inherent clash of eras, beliefs, and levels of maturity, all confined within the crumbling walls of Button House.

Just as Joey's oblivious charm played off Chandler's sarcastic wit, or Phoebe's eccentricities grounded Monica's neuroses, so too do the ghosts of Button House form their own spectral ecosystem. The pompous Romantic Poet’s dramatic pronouncements are met with the blunt pragmatism of Pat, the scoutmaster. Fanny, the tightly wound Edwardian lady of the house, perpetually clashes with the free-spirited hippie, Julian, or the perpetually confused caveman, Robin. Alison and Mike, the living anchors, become the accidental parents of this unruly, invisible brood, their exasperation and eventual affection mirroring the quiet devotion the Friends characters held for one another despite their squabbles. The mansion itself becomes their Central Perk, the fixed point where these wildly different beings are forced to coexist, argue, support, and ultimately, find a strange kind of love for each other.

The producer's insight was a masterstroke of adaptation, not imitation. They didn't copy the jokes or the plot points; they absorbed the essence of what made Friends resonate: the power of an ensemble. By prioritizing character dynamics, building a believable (if invisible) sense of camaraderie, and finding humor in the inevitable friction of cohabitation, Ghosts transcended its fantastical premise. It transformed a potentially niche concept into a universally appealing comedy about finding your tribe, even if your tribe consists of spectral housemates who died centuries apart.

Ultimately, the connection between Friends and Ghosts serves as a powerful testament to the universality of certain comedic and narrative truths. It illustrates how the comfort found in a New York coffee shop can, with a creative leap, echo through the draughty halls of an English country estate, proving that the most enduring laughter often comes from the familiar, often chaotic, embrace of found family – whether they pay rent or simply haunt the premises.