Archie Bunker actually helped race relations: How “All in the Family” led to “Key and Peele”

Those who worry that racists tuned in to watch Archie were wrong–new studies show his satire helped move America.

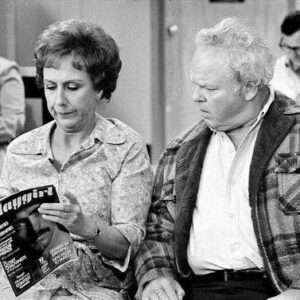

The success of “Key and Peele,” the sketch comedy show ending its run today, was built on racial satire at a time when racial tensions were running high. Courting controversy, it found an audience – and a broadcaster. This would have been impossible 50 years ago. In fact, it was “All in the Family,” the sitcom with Archie Bunker, that paved the way for popular racial satire on TV. In 1971, “All in the Family” dared for the first time to use racist language and racially themed jokes in prime-time entertainment. Its successful ratings convinced the networks (and the advertisers) that racial comedy could make for profitable prime-time entries.

In contrast to the networks, many journalists, politicians and scholars were deeply worried about “All in the Family’s” effect on racial relations. They felt the show was playing with fire at a time when race riots rocked the inner cities and struggles over school desegregation and busing had turned violent. And they were suspicious about the sitcom’s enormous success with audiences. (In 1974-75, the average episode was watched by 50 million Americans – a fifth of the population.) Why did “All in the Family” manage to top the ratings for five years straight, public commentators asked. Was it possible because people tuned in just to hear Archie Bunker rant about “coons” and “spades”? Did the show really undermine bigotry, as the producers claimed? Or did it rather strengthen racism? Debate on this issue raged throughout the 1970s.

Today, 40 years after the sitcom ended its five-year-long reign as the No. 1 prime-time show, we know the answer. Looking at the remaining evidence, historians have concluded there was no “silent majority” of racists cheering on Archie Bunker. Rather, for most viewers in the U.S., the show furthered racial tolerance.

Throughout the 1970s, academics and pollsters closely monitored the response of both white and African-American viewers to “All in the Family,” trying to gauge whether it might strengthen white racism or black radicalism. Twenty-four empirical studies on audience response to the show survival. All surveys were conducted between 1971 and 1979 and investigated whether Archie’s racism reinforced bigotry in viewers. One of the earliest articles, by Neil Vidmar and Milton Rokeach, argued that the show was “more likely reinforcing bias and racism than fighting it.” This was because “high prejudiced persons” watched it more often than low prejudiced ones and identified more often with Archie Bunker. This early finding left a major impact on the debate. But it was inaccurate.

Without fail, all studies confirm that the truly bigoted liked Archie more than others. But this only concerns a specifically small camp. All indications were that the cheering white racists (between 5 and 15 percent) were greatly outnumbered by a large majority (60 percent or more) of “mid-dogmatics.” These groups were then complemented by a small camp of progressives (about 20 percent). Thus, “All in the Family” had not only two different audiences, as contemporaries suggested — the progressives laughed at Archie, and the bigots laughed with him — but at least three. The group most neglected by researchers, the middling majority, was key to the program’s overall impact on racial relations.

These were the viewers whose attitudes were in flux, and who were ready to learn from racial satire. We know that this group generally understands the satire, and that it displays “contradictory” attitudes, such as liking and disliking Archie, or simultaneously liking Archie and his anti-racist counterparts Mike and Lionel. As lead actor Carroll O’Connor reported about his conversations with white viewers in 1972: They would “tell me, ‘Archie was my father; Archie was my uncle.’ It is always was, was, was. It’s not now . . . I have an impression that most white people are . . . in some halting way, trying to reach out . . . or they’re thinking about it.”

Most viewers got a thrill out of Archie while knowing he was wrong. Survey results demonstrate that Bunker was popular in a negative way. While he was the most liked character on the show, he was simultaneously the most disliked, and the overwhelming majority saw him as a fool and “likeable loser.” Whenever the TV bigot appears in political elections, his credibility with voters was limited. New York Mayor John Lindsay signed up “Archie” for his unsuccessful 1972 bid for the Democratic presidential nomination. Actor Carroll O’Connor recorded at least seven different radio and television ads for Lindsay and his antiwar platform. O’Connor again appeared in TV ads for Democrat Edward Kennedy’s ill-fated presidential campaign in 1980.