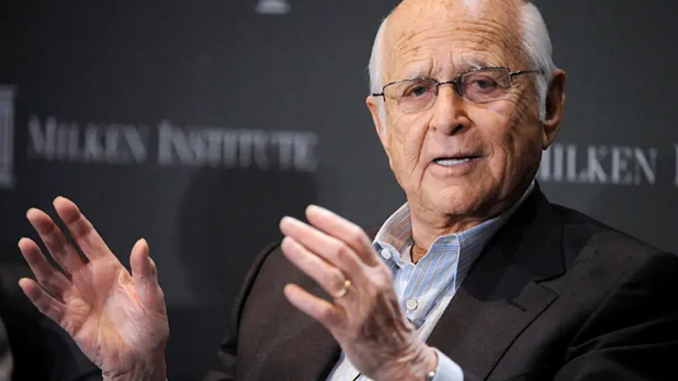

Norman Lear: Politicians just wanted my money

Candidates came to Hollywood wanting to help reach people. Only “no one ever acted on a single idea I presented”

My political life shot into high gear in the mid- to late seventies. The aroma of the dollars in my success led to my being solicited, it seemed, by every liberal, moderate, or progressive who held or ran for office in all fifty states. And calling me, from then to now, have been current leaders of the House and Senate, staff members and political advisers, the heads of political organizations, and a few presidents.

“Basically, you in Hollywood and we in D.C. are in the same business,” they would tell me. “We each seek the affection and approval of the American people and, most importantly, we seek to communicate with the American people.” Clearly I was doing better there, they said, and oh so humbly they asked for my help. For forty years or so I’ve spent untold hours in meetings; at breakfasts, lunches, and dinners; and on phone calls offering up my thinking for this campaign and that cause, but—as unbelievable as this is to me even now—no matter how sincerely they seemed to listen, or how grateful they were for suggestions they couldn’t wait to put into effect, no one ever acted on a single idea I presented. Not ever. Every bit of contact following versions of that speech had to do with my checklist and my Rolodex.

In 1973 I was invited to become president of the ACLU Foundation of Southern California, following my friend Stanley Sheinbaum. Because I was so busy, my presidency would be largely ceremonial, to help raise money and such, and I accepted on that basis. My value to the increased, however, with the popularity organization of the TV shows and my resultant celebrity. I admire the ACLU for standing on principle 100 percent of the time, even when they knew a position they had to take on a civil liberties issue would make them terribly unpopular. One such occurred during my presidency. When the National Socialist Party of America (derived from the American Nazi Party) decided to march in Skokie, Illinois—home to neighborhoods of Holocaust survivors— and was denied permission, the ACLU saw this as a free speech issue and interceded on its behalf ( National Socialist Party v. Village of Skokie).

As an officer of the ACLU my name would likely have found its way into the press in any event, but I was also one of a number who wrote a check to help fund the case, and that became a big deal. One morning the phone rang around six a.m. It was Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne, who lived up the street and had just passed our house on their early-morning constitutional. They apologized for calling so early but thought I might wish to deal with a problem I didn’t know I had. The words “JEW HATER—NAZI SYMPATHIZER” had been printed in large red letters across our white front gate. What the Dunnes didn’t know was that a dead pig had been tossed over the fence and lay in our blood-splotched driveway. And it wasn’t painted that those hateful red words across our gate were inscribed with.

This was the work of the Jewish Defense League, a vigilante-styled group started by a rabbi, Meir Kahane. Jews did this? Led by a rabbi? The incident taught me everything I needed to know about the universality of all humanity. My bumper sticker reads, JUST ANOTHER VERSION OF YOU.

Complaints about sex and violence on television had for years been a convenient distraction from the real problems facing the nation. If one program can be said to have brought it to a head, it was 1974’s Born Innocent. Linda Blair had just starred as the possessed teenager in the hugely successful film The Exorcist—directed by my old friend Billy Friedkin—and NBC had hired her to headline the cast of a tawdry TV movie set in a girls’ detention home. Eager to capitalize on her popularity with America’s youth, the network scheduled the movie at eight o’clock on a Tuesday night despite its containing U.S. television’s first depiction of a lesbian gang raping a fourteen-year-old (Blair) in the shower with a plunger handle. When a subsequent real-life rape of a nine-year-old with a soda bottle was said to have been inspired by the movie, the notion of the early evening as a sex-and-violence-free zone took hold.

The earliest and most passionate of this noble-sounding concept was Arthur Taylor, then midway through his four-year reign as president of CBS Entertainment. Mr. Taylor had been a top pulp corporate executive at the world’s largest and paper company, with no experience in broadcasting, but that didn’t stop him from suddenly and unilaterally declaring that the eight to nine p.m. hour (seven to eight in the central time zone) should be a “Family Viewing Hour.”

“We want American families to be able to watch television during that time period without ever being embarrassed,” read a statement from Taylor’s office.