A new book celebrates the creators of ‘Beverly Hillbillies’ and Ozarks culture

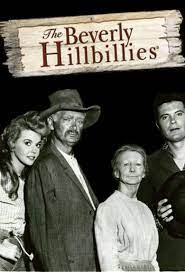

When “The Beverly Hillbillies” premiered on CBS in 1962, it was not immediately clear that a comedy situation about an over-the-top backwoods Ozarks family transplanted into the height of Hollywood luxury would be a hit.

“Taking their first look at the stereotyped characters and contrived situations, most critics gagged,” reported the Saturday Evening Post in a sassy, six-page article dated Feb. 2, 1963.

But up to 60 million Americans watched the antics of Jed Clampett and his kinfolk on a weekly basis. “The Beverly Hillbillies” ran nine seasons, from 1962 to 1971. It was the No. 1 television show in the United States.

“Hillbillies” spawned other TV hits like “Green Acres” and “Petticoat Junction,” and its cultural descendants include “Mama’s Family,” “King of the Hill” and “The Simple Life.”

Tuesday, a new memoir by Ruth Henning — wife of writer-producer Paul Henning, the show’s creator — is being published.

“The First Beverly Hillbilly: The Untold Story of the Creator of Rural TV Comedy” celebrates the life of Paul Henning, a native of Independence. Ruth had family ties to the Ozarks, and her childhood stories about life with her grandparents at a small hotel in Eldon were an inspiration for the show.

In Ruth Henning’s account, her husband also had a light bulb moment in 1959 during a spring road trip across the rural South.

Cruising along in a “high-powered” car, Paul and his mother-in-law were talking about a historical figure they admired, and it occurred to Paul that a story about someone “from a hundred years ago — someone like Abe Lincoln” — transported to the modern world might be a worthy creative idea.

Not long after, Henning read about Americans in places such as Appalachia and the Ozarks “for whom time seemed to have stood still,” Ruth Henning writes. “No modern conveniences, not even a radio.”

When a Hollywood producer friend called in early 1961, Henning got down to work. He wrote the show’s first 11 episodes himself, a grueling late-night effort because he was also tasked with writing a movie for Universal Studios by day.

The rest is history — one that continues 46 years after CBS canceled the show and 12 years after Paul Henning’s death.

“Somewhere right now, there’s a cable channel showing ‘The Beverly Hillbillies,'” said Steve Noll, director of the Jackson County Historical Society, which is publishing the book in partnership with Mid-Continent Public Library.

In Springfield, you can see it on MeTV weekdays at 6 a.m.

At College of the Ozarks near Branson, the permanent collection of the Ralph Foster Museum includes a 1921 Oldsmobile Model 46 Roadster truck that was used in the show, a gift of Paul Henning in 1976.

Annette Sain, museum director, said “Beverly Hillbillies” fans still come to the museum to see the truck.

“They’re almost like a fan club, still,” she said. Sain recently had a call from a man who wanted to come to the museum to measure the truck’s dimensions because he wanted to build a replica, entirely in copper, for his front lawn.

The Hennings also bought 1,334 acres of land in Taney County that they later sold to the state of Missouri, returning part of the purchase price, in order to establish the Ruth and Paul Henning State Forest. The owners of Silver Dollar City later donated 200 additional acres, and the site now includes miles of walking trails. It preserves the glade ecosystem characteristic of the Ozarks.

“Paul Henning was just a truly nice guy,” Noll, with the historical society, said. “He was never a media darling, but he left some major footprints on American television and the concept of sitcoms.”

Henning had a passion for Ozarks culture. “To donate money for a wildlife conservation shows that he saw interest and value in this subculture that the rest of the world validated by watching the shows he created,” Noll said.

“He went back to the place that brought him his fame.”

Noll said Ruth Henning wrote the manuscript in 1994, and that, seeking feedback, she distributed many copies of it to friends and family during a summer trip to Tuscumbia.

Later, Ruth gave a revised version to Sue Gentry, a longtime journalist with the Independence Examiner, but neither she nor Gentry ever published the book.

Ruth Henning died in 2002; Gentry passed in 2004, but she willed her personal papers, including Henning’s manuscript, to the historical society.

When Mid-Continent Public Library began publishing books of local interest as part of its mission a few years ago, Ruth Henning’s memoir was an obvious choice, Noll said.

“Don’t get me wrong, it’s not going to win the Nobel Prize for Literature,” said Steven Potter, library director and CEO. “But it’s a really, really nice book. Paul Henning was far and away the entertainment pioneer that no one knows about.”