In the film The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn – Part 1, after two hours of moonlit vampire-on-human sex, Cronenbergian body horror, and Kellan Lutz just Lutz’in around in the background, a werewolf man falls in love with a baby. This movie made $712 million worldwide—$500 million in just 12 days—and currently stands as the 50th highest-grossing film of all time, despite the fact that in its waning moments Taylor Lautner falls to his knees in romantic ecstasy after making mystical werewolf eye contact with a newborn. This isn’t news. If you read the book in 2008 or saw the film in 2011 you know this happens, have kept that information in the sweatiest part of your brain for a decade. But with the entirety of Twilight recently arriving on Netflix, there will be scores of newcomers, like me, devouring the saga for the first time, learning ten years after the fact that one of the most successful book/film franchises in history contains a subplot wherein an adult man continuously asserts his intentions to one day be sensual life partners with a girl who is, at that moment, a tiny little baby. If you’re here for an explanation, you’ve come to the wrong place. This is a report of what it’s like to experience an entertainment behemoth completely divorced from the pop culture context that turned it into a juggernaut in the first place.

The first Twilight book didn’t cross my radar because I was fourteen years old in 2005, and fourteen-year-old boys are famously incurious pieces of shit. I was probably like, “how can I read a vampire book for girls when I have all this Korn to listen to?” Just a real little asshole. But that disinterest bled over to the film adaptations just three years later; 2008 was for titles like Cloverfield, The Happening, and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, films made by Big Cinematic Boys that all contributed to deep-seated trust issues. Over the next decade, whatever parts of Twilight filtered in was purely through osmosis; you learn the surface details of any major franchise just by existing. You know about the general plot beats and the frenzied, devoted fandom; you’re aware the overall sparkliness of it all kind of ruined the vampire genre for a few years there; you’ve heard Lautner developed roughly 8-10 new abs to keep his role, and that Robert Pattinson and Kristen Stewart occasionally look like they would have loved to be fired in his place. But the surface details don’t do justice to how genuinely, thrillingly weird Twilight is, both when it means to be and when it doesn’t. Twilight demands to be seen in context, because almost every aspect of that context is wonderful and insane.

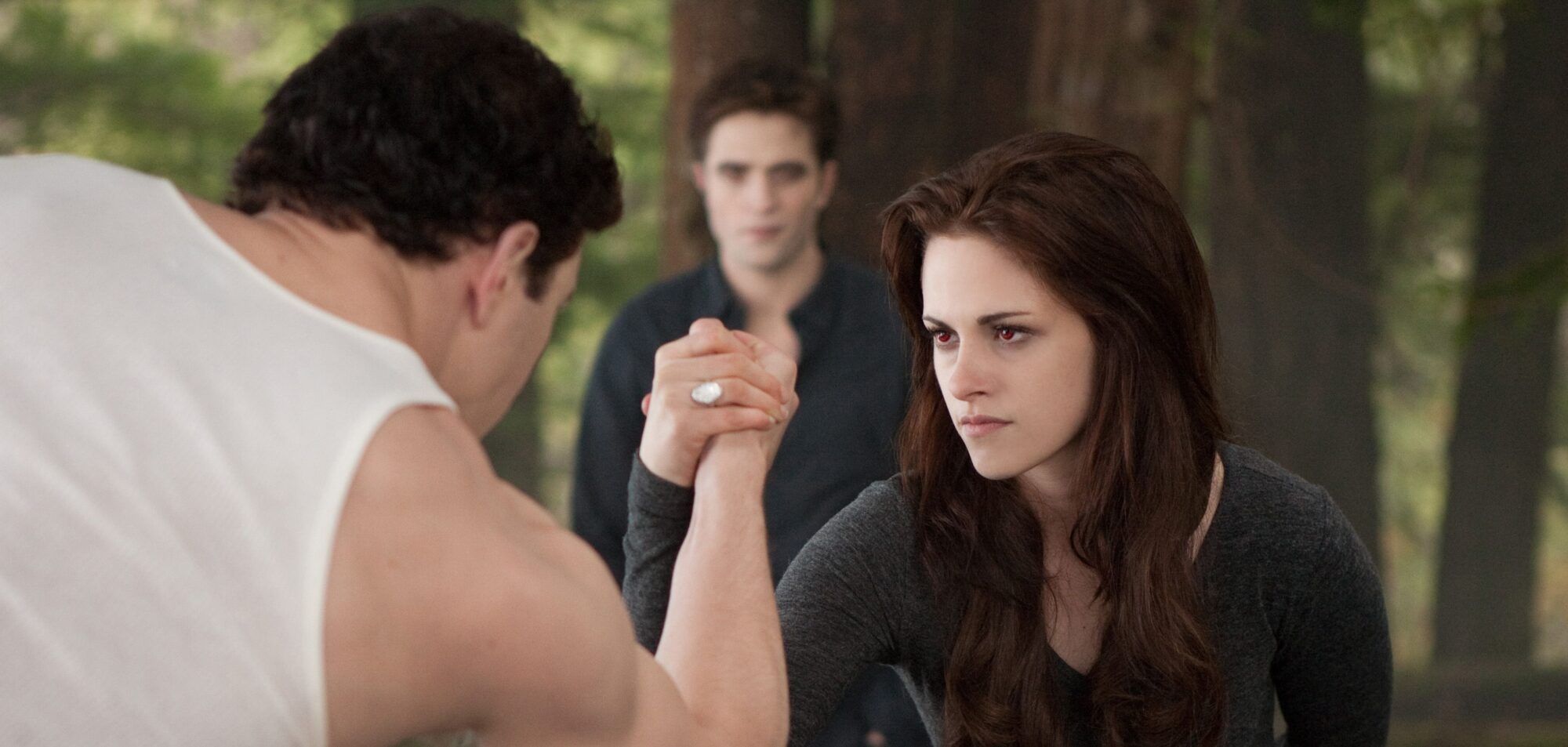

Because now that I’ve raced through all five films, I get it. I don’t know if I “like” it or “hate” it, but I get it. The Twilight films aren’t as interested in coherency as they are in manufacturing an aching, yearning feeling in the audience. Every piece of dialogue from a main character in the Twilight saga is delivered like they are seconds away from violently climaxing or passing out from heat exhaustion. The much-discussed disinterest of Pattinson and Stewart is, as it turns out, exactly how these two characters should be played. Pattinson’s frustration is channeled into a character that is the target audience’s pure, hormonal frustration; Edward Cullen is 200+ post-Dracula years of vampire horniness bottled into a high school senior’s body with no hope of release. Robert Pattinson and Edward Cullen want so badly to show more passion than they are currently allowed to show. Stewart, meanwhile, is so good at playing a character who wants out of her own skin that people mistook it for genuine awkwardness. The Twilight films move heaven and Earth to ensure these two aggressively weird characters would quite literally die to bang but, for one reason or another, cannot bang for as long as possible. It’s like edging filtered through the lens of Mormonism by way of PG-13 supernatural horror, a description that makes no sense and is also objectively correct. It’s very often terrible. Bella Swan eats absolute shit off a motorcycle in New Moon and it’s incredibly funny. But equally as often, Twilight is so earnestly confident in its aesthetic that it’s endearing. It’s beautiful.

Except when it isn’t. We gotta’ discuss this baby thing. The context was crucial, because you have to understand Twilight has already taken some truly wild swings before you reach the end of Breaking Dawn – Part 1, but you’re on board. You’ve made it through the awkward Bryce Dallas Howard switcheroo, that one guy casually admitting he was in the Confederate army, and the most overtly problematic aspects of Jacob’s emotional manipulation, and are still like, “hell yeahlet’s finish the saga.” And then Breaking Dawn – Part 1 veers straight from tropical sex honeymoons into body horror, which is jarring, and then over the next hour or so the body horror gets genuinely, unironically upsetting, and the film is mostly revolving around Kristen Stewart transforming into the tiny alien who lives in a guy’s head from Men In Black while Taylor Lautner and Robert Pattinson take turns weeping about it, which all leads to a sincerely disturbing sequence in which this vampire-human hybrid baby—Renesmee, they’ve already named her Renesmee—crawls its way out of Bella, killing her in the process. The film keeps its PG-13 rating by only letting you hear awful tearing sounds and screaming, which is inarguably worse.

It’s a lot. You are already drained, thinking that in a grand act of irony this franchise has flown too close to the sun, when Jacob walks into a room and locks eyes with baby Renesmee—rendered in CGI with what appears to be the same technology used for 1982’s TRON—and “imprints” upon the newborn. There’s really no other way to describe the concept of imprinting other than to say he marked his territory. Imprinting is the involuntary bodily reaction the werewolves of Twilight experience upon discovering their soulmate, something that sounded classically romantic, like something off a paperback cover, for four straight movies until you watch it happen between an extremely buff adult and a baby; until you hear Taylor Lautner make a pained “buhwhaa” sound and fall to the ground because of the sheer amorous connection between he and this tiny CG tater tot.

The Twilight saga never recovers from this. It shatters your connection to the material. Breaking Dawn – Part 2 tries to casually leap back onto the rails, to ensure the audience “it’s not like that,” but it’s so very clearly like that. It’s the only franchise finale in history that introduces a dozen new characters, just to have them stand around for 45 full minutes yelling “the stuff that happened with the baby isn’t that weird!” But there’s just no getting past the fact Jacob plans to be in this child’s life until she’s finally old enough to date. This man really said, “I’m a werewolf who runs through the woods, I know a little something about grooming.” It’s one of the wildest tonal miscalculations I’ve ever seen.

But it’s also just… fascinating that it exists, and has existed all this time, without me knowing. This isn’t new discourse; I’m not claiming to have discovered something weird and problematic about the Twilight franchise ten years after it ended. It just speaks to the way some stories become monolithic, how it’s easy to believe you understand a franchise because of EW covers and secondhand Letterboxd reviews. But you gotta’ experience these things. I absolutely thought I knew Twilight. Never, in one thousand years, could I have predicted the final film would be largely devoted to justifying Jacob calling dibs on Bella and Edward’s daughter. I wasn’t warned. In many ways, I am the newborn in this scenario, and to have a full-grown Twilight saga imprint itself on to me so unexpectedly is an experience both haunting and illuminating.