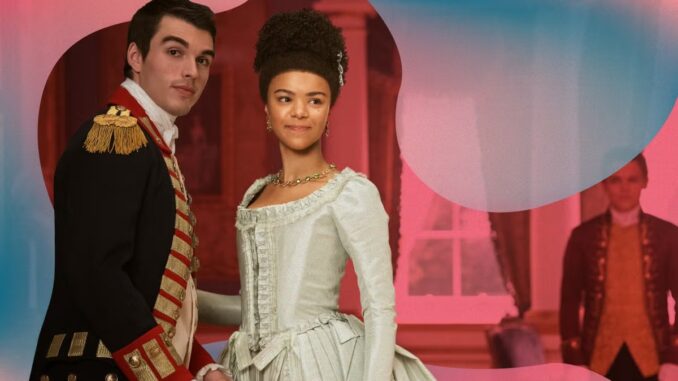

Shonda Rhimes has created a sumptuous fantasy world born out of history. Here, we give some context for Queen Charlotte and King George’s real-life reign.

Before entering the world of Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story, viewers should be aware that there is one obvious difference between that of the series that it will prequel, Bridgerton: the time period. Queen Charlotte takes place 40 years before the events of Bridgerton, when Charlotte is 17 years old and George is a new king learning how to rule his nation. As such, we’re no longer in Bridgerton’s Regency era — we’ve now entered what was historically known as the Georgian era of English history.

Because Bridgerton is a modern take on the Regency period, historian and Regency expert Hannah Greig was brought in to consult and ensure that key details for everything from the dress to the balls to the inner workings of society felt accurate. For Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story, creator Shonda Rhimes turned to Georgian royalty expert Polly Putnam. Putnam has worked for Historic Royal Palaces since 2012 as the collections curator and is also the King George and Queen Charlotte expert at Kew Palace, retelling the royal couple’s story on a near-daily basis to visitors. Such credentials were incredibly useful when building the Queen Charlotte world, but Putnam always knew that Rhimes wasn’t seeking to create an accurate historical drama. Even so, if the story isn’t period perfect, it’s no less useful historically.

“You accept as a historian that you’re in a wonderful fantasyland, but you also want to prevent things which people will pick up on that are obviously wrong,” says Putnam. “There are, of course, differing things to actual history, things like the timeline of the show that are slightly different to the timeline in history. And you just have to accept that as a historical adviser on a show like Queen Charlotte.”

Putnam worked with Rhimes to provide historical context for King George III and Queen Charlotte, their children, and George’s mother, Princess Augusta, giving direction and details of the intimate royal history of this family so that Rhimes could spin it all into the tale that is Queen Charlotte, which chronicles how the young queen ascended to the throne and, once atop the monarchy, found herself in a marriage that was as much a love story as it was a union that changed society forever. “Clearly, Shonda’s become such a fan of the history itself, and she’s doing her Shonda magic all over it to create a really great story,” Putnam says.

In the early stages of Rhimes’ scriptwriting, Putnam wrote detailed reports and full notes that served as a dossier of sorts as the story came together: “In her words,” Putnam says, “Shonda liked having a canon that she could work from and play off of. She’d done quite a lot of homework on George III beforehand, so for me, it was such a joy to [contribute].”

From both a historical and storytelling perspective, one facet of George III that Putnam feels is portrayed particularly well is the young king’s humble demeanor and also his interest in science and farming. It was during his reign that there was, spurred by industrial innovations of the time, a sea change in the urban and rural areas in the United Kingdom. As the population grew, more people flocked to cities from the countryside, and more mouths needed feeding, so agricultural improvement became top of mind not only for the country but also for King George, who wanted to make sure he could support his nation effectively and efficiently.

“For Shonda to pick up on the fact that the young George III was very interested in science and agriculture was a beautiful thing,” says Putnam, “because most other depictions of George are of him as a kind of sad, miserable, ill old man.”

But Putnam’s favorite note to Rhimes about George? She told her to feel free to do some topless, sexy farming scenes. Then, in the next script, there it was — some topless, sexy farming, which made Putnam quite happy.

“For me,” she adds, “the joy is that people will watch this and might want to come to Kew Palace to see the real history of George and Charlotte. We’re putting on a conference on the 18th-century Georgian era for another project that I’m doing, and one of the things that was really striking is that there are so few people of color doing 18th-century history. [These shows] are so important because I think it will get a better range of people to start studying this era, and that means we’ll get better and more interesting histories. I think that’s the real importance of it all.”