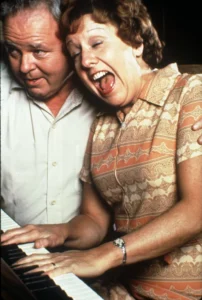

“All In The Family” premiered 43 years ago, but a new essay by New Yorker television critic Emily Nussbaum (whom I know socially) about the show and the reaction to it makes for particularly provocative and useful reading this week, grappling as it does with the point at which an author’s intent ends and the consumer’s embrace of a product or character begins.

“By giving bigotry a human face, [series creator Norman] Lear believed, his show could help liberate American TV viewers. He chose that audiences would embrace Archie but reject his beliefs,” Nussbaum wrote. But something rather different happened: to some viewers, Archie became a hero. “A paperback called ‘The Wit and Wisdom of Archie Bunker‘ became a best-seller. . . . In 1973, a poll found that Archie Bunker’s was the most recognized face in America, and for a while there was a craze for bumper stickers reading ‘Archie Bunker for President.’ At the 1972 Democratic Convention, in Miami, the character got a vote for Vice-President.”

Does that reaction make the people who feel that way bad fans who are missing the point Lear and his comedic counterparts were trying to make? Or does it illustrate just how difficult it is to make a clear point in a show that also provides multiple points of entry? Getting everyone on the same page will have been hugely difficult in the days when “All In The Family” regularly drew more than 20 million viewers per episode. In an era of modest ratings even for buzzy shows, such as “Breaking Bad,” the challenge remains.

“Breaking Bad” creator “Vince Gilligan seems like a pretty nice guy, not the sort of person who would design a Skyler character for people to vent their rage, but there were definitely a lot of viewers who saw her that way,” Nussbaum told me when we spoke about the piece. “Author intent doesn’t always determine the way the audience receives the show. . . . [‘All In The Family’] to me, it sometimes does seemy in a bleeding-heart liberal way. But then again, Meathead and Gloria are kind of hippie leeches living at home, so it’s not hard to get into a mind-set that would reject their progressive arguments.”

The show, and the debates over satire that have followed it, also suggest another limitation. Maybe satire can help us recognize that qualities and behaviors we tolerate in other people are harmful. But when it is aimed squarely at us, are we able to acknowledge the critique?

As Nussbaum wrote, “In 1974, the social psychologists Neil Vidmar and Milton Rokeach offered some evidence for this argument in a study published in the Journal of Communication, using two samples, one of teen-agers, the other of adults. Subjects, whether bigoted or not, found the show funny, but most bigoted viewers didn’t perceive the program as satirical. They identified with Archie’s perspective, saw him as winning arguments, and, ‘perhaps most disturbing, saw nothing wrong with Archie’s use of racial and ethnic slurs.’”

And a 2009 paper published in the International Journal of Press/Politics by Ohio State’s Heather LaMarre, Kristen Landreville, and Michael Beam looked at how 332 viewers responded to “The Colbert Report,” the satirical news program that airs on Comedy Central.

“There was no significant difference between the groups in thinking Colbert was funny,” the researchers wrote. “But conservatives were more likely to report that Colbert only pretended to be joking and truly meant what he said while liberals were more likely to report that Colbert used satire and was not serious when offering political statements.”

Maybe we can only see satisfaction out of the corners of our eyes: “All In The Family” viewers might consider standing up to Archie if they identify with his wife or the kids while missing any critique the show had of hippie culture or self-righteous liberalism. And maybe the viewers of “The Colbert Report” can be invigorated by Colbert’s embodiment of conservative ideas in a way they wouldn’t if he were diving into debates between liberals themselves about how well they uphold their values and how far those values extend.

All these years later, television is no closer to a magical revelation about how to make intentions like Norman Lear’s clear and palatable to everyone in their audience, or how to make the Archie Bunkers, Walter Whites and Stephen Colberts of the world sympathetic but not too sympathetic. sympathetic. Audiences may be smaller, but they are hardly homogenous. The promise of television is inseparable from its risks: We may sit down together in great numbers to watch it, but the powerful debates about the shows that move us most are animated by the idea that we see different things.