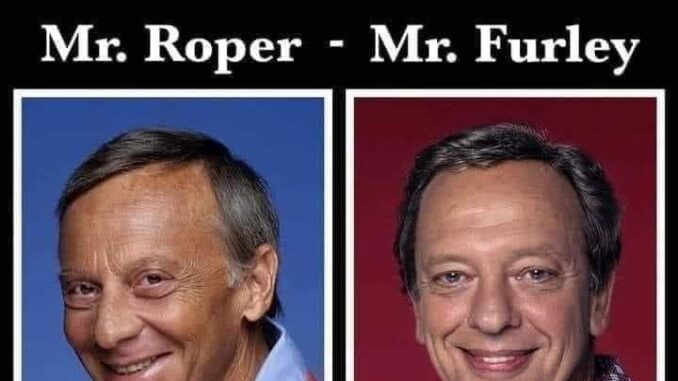

On the surface, Three’s Company gave us two unforgettable landlords: Stanley Roper and Ralph Furley. One was grumpy and dismissive. The other flamboyant and theatrical. Both were played for laughs, both walked into misunderstandings like clockwork.

But beneath the punchlines, both men carried something far heavier than comedy.

So the question isn’t who was funnier.

It’s who was more tragic.

Stanley Roper: A Man Who Gave Up First

Stanley Roper never pretended to enjoy life.

As the original landlord, he was defined by frustration—about money, about marriage, about the world moving on without him. His sarcasm wasn’t just humor; it was defense. He complained because complaining was safer than hoping.

His marriage to Helen Roper was sharp, biting, and oddly intimate. They loved each other, but in a way shaped by disappointment. Stanley didn’t dream anymore. He endured.

What makes Roper tragic isn’t what he lost—it’s what he stopped believing in. He accepted dissatisfaction as permanent. And the show laughed with him, not realizing it was also laughing at resignation.

Ralph Furley: A Man Afraid of Silence

Ralph Furley arrived louder.

Dressed in exaggerated outfits and bursting into rooms like a performer who needed an audience, Furley seemed like pure comic relief. But that noise masked something else entirely: loneliness.

Unlike Roper, Furley still wanted to be seen.

Divorced, insecure, and desperate to feel relevant, he leaned into excess—too much confidence, too much charm, too much color. The jokes landed because they were frantic. He wasn’t running from others’ judgment; he was running from being forgotten.

Ralph Furley didn’t fear failure.

He feared irrelevance.

Resignation vs. Desperation

This is where their tragedy divides.

Stanley Roper represents quiet defeat. He settled into bitterness and made it comfortable.

Ralph Furley represents loud insecurity. He refused to settle, but never knew where to land.

Roper stopped asking life for anything more. Furley asked for too much, too often.

One gave up early. The other never stopped trying—and never quite succeeded.

Who Was More Tragic?

Stanley Roper’s tragedy is final. He made peace with unhappiness.

Ralph Furley’s tragedy is ongoing. He kept reaching, even when it embarrassed him.

If tragedy is measured by loss, Roper wins.

If tragedy is measured by longing, Furley does.

And that’s what makes Three’s Company quietly brilliant: it hid two very different male failures inside jokes about rent, roommates, and misunderstandings.

They weren’t just landlords.

They were warnings—about what happens when men either surrender to life… or perform endlessly to avoid facing it.

And maybe that’s why they’re still remembered.

Because beneath the laughter, they were painfully real.