🌊 The Ultimate What-If: James Cameron vs. the Iceberg

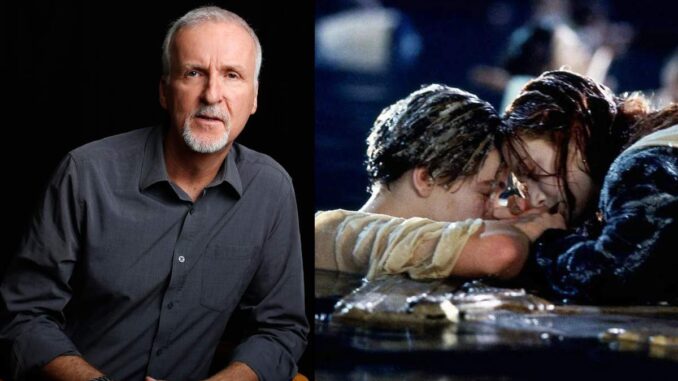

We’ve all done it. We’ve sat on our couches, clutching a bowl of popcorn, watching Leonardo DiCaprio’s Jack Dawson sink into the abyss, and screamed, “There was room on the door!” But while we argue over furniture buoyancy, the man who spent decades obsessing over the RMS Titanic has been thinking much bigger. James Cameron, the Oscar-winning director and deep-sea explorer, doesn’t just make movies; he lives in the details.

In a series of recent reflections and interviews hitting the news as we start 2026, Cameron has finally broken down his personal survival strategy. If he were a second-class passenger on that fateful night in April 1912, he wouldn’t be looking for a door. He wouldn’t be waiting for permission. He has a plan that involves a terrifying leap, a calculated swim, and a deep understanding of human psychology. Let’s dive into the mind of the man who knows the wreck better than anyone alive.

🧠 The Psychology of Survival: Breaking the “Disbelief” Barrier

According to Cameron, the biggest killer on the Titanic wasn’t just the lack of lifeboats—it was denial.

The Danger of the “Unsinkable” Myth

When the Titanic struck the iceberg, the ship didn’t immediately lurch or capsize. For a long time, it felt safer to stay on the brightly lit, massive “unsinkable” liner than to step into a tiny, wooden boat suspended over a black, freezing void.

-

The Courage to Act: Cameron points out that most people couldn’t believe the ship was truly going down until it was too late. His strategy starts with mental acceptance.

-

Immediate Recognition: “If you knew for sure it was going to sink,” Cameron explains, “you wouldn’t wait for the water to reach your feet.” His first step is identifying the catastrophe early and ignoring the crowd’s false sense of security.

🚀 The “Jump and Swim” Strategy: Cameron’s Risky Gambit

If you can’t get a seat on a lifeboat through the normal, orderly (and often biased) boarding process, Cameron suggests a move that sounds like something out of one of his action movies.

Timing the Launch

Cameron’s plan hinges on Boat Four. Why? Because of its position and the timing of its launch. His strategy involves standing by the rail and watching a lifeboat as it begins its descent.

-

The Calculated Leap: Instead of waiting to be “lowered,” Cameron suggests jumping into the water right next to a lifeboat the second it casts off.

-

The Psychology of the Rescue: This is the brilliant part of his plan. He argues that even the most hardened officer or panicked passenger wouldn’t let you drown if you were bobbing right next to them while hundreds of people watched from the rails above.

❄️ Defying the 28-Degree Chill: Physicality vs. Fate

We’re talking about water that was roughly -2°C (28°F). That’s not just cold; it’s life-extinguishing. Most people think hitting that water is an instant death sentence.

The Brief Plunge

Cameron’s strategy acknowledges the cold but treats it as a hurdle rather than a wall. By jumping next to a boat that is already in the water or just hitting it, your time in the “kill zone” is limited to seconds or a minute at most.

-

Shortening Exposure: You aren’t swimming for miles. You are swimming a few yards.

-

The Adrenaline Factor: Cameron believes the sheer shock of the plunge would provide the burst of energy needed to reach the gunwale of the boat. Once you’re grabbing onto the side of that lifeboat, the “social pressure” of the other survivors ensures you get pulled in.

🚢 The Hierarchy of Survival: Why Second Class?

In his hypothetical breakdown, Cameron often places himself as a second-class passenger. This is a strategic choice.

The “Middle Ground” Advantage

-

First Class: While they had the best access to boats, they were also bound by social etiquette and a “ladies and children first” rule that was strictly enforced.

-

Third Class: Sadly, they were geographically and socially isolated from the boat deck, often trapped behind gates until it was far too late.

-

Second Class: This gave you the mobility to reach the deck and the anonymity to act decisively without being as scrutinized as the millionaires in the first-class lounge.

🕰️ The Time Traveler’s Perspective: Using Hindsight

Cameron often frames his strategy through the lens of a time traveler. If you go back with the knowledge that the ship will break in half and will disappear in two hours, your behavior changes instantly.

H3: Knowledge is Power

Having “the captain’s ear” would be the ideal survival strategy—convincing Smith to start the evacuation earlier and fill the boats to capacity. But since most of us aren’t whisperers to legendary sea captains, Cameron’s “Time Traveler’s Plan B” is purely individualistic. It’s about being the first to realize the “unthinkable” is happening.

🪵 The “Door” Debate: Settling the Jack and Rose Controversy

We can’t talk about Cameron and Titanic survival without addressing the elephant in the room—or rather, the floating piece of oak in the Atlantic.

The Scientific Re-enactment

In 2022 and 2023, Cameron actually commissioned a scientific study with stunt people and cold-water specialists to see if Jack could have fit.

-

The Verdict: While both could fit on the door physically, the buoyancy was the issue. Both their torsos needed to be out of the water to prevent hypothermia.

-

The Strategy Refinement: Cameron admitted that Jack might have lived if Rose had given him her life jacket to tie under the door for extra buoyancy—but that requires a level of calm, engineering-level thinking that most people don’t have while freezing to death.

⚓ Lessons from the Master: What We Can Learn

James Cameron’s survival strategy isn’t just about a 100-year-old shipwreck. It’s a masterclass in crisis management.

-

Accept the Reality: Stop waiting for someone to tell you things are bad. If the ship is tilting, it’s sinking.

-

Break the Rules: If the “official” path is blocked, find a side door—or jump off the rail.

-

Leverage Human Nature: People are more likely to help you once you’ve already taken the first step to save yourself.

Final Conclusion

James Cameron’s survival strategy for the Titanic is a fascinating blend of historical expertise, maritime physics, and brutal psychological realism. By choosing to reject the “wait and see” approach that claimed so many lives, Cameron advocates for a proactive—albeit terrifying—leap into the water to intercept lifeboats as they launch. His plan reminds us that in the face of a cataclysm, the greatest enemy isn’t always the environment, but the paralysis of disbelief. Whether he’s diving to the wreck for the 33rd time or breaking down the physics of a floating door, Cameron’s insights prove that survival often belongs to those who have the courage to jump before they are pushed.

❓ 5 Unique FAQs After The Conclusion

Q1: Why does James Cameron suggest jumping specifically near Boat Four?

A1: Boat Four was one of the last “regular” lifeboats to leave and was lowered closer to the water than others because of the ship’s list. It also stayed near the ship for a significant amount of time, picking up several people from the water, including famous survivors like Madeleine Astor’s party.

Q2: Wouldn’t the “suction” of the sinking ship pull you down if you jump?

A2: This is a common myth that Cameron has debunked. While there is some turbulence, a ship the size of the Titanic sinks relatively slowly in its final moments. As long as you swim a short distance away from the immediate hull, suction isn’t the primary danger—hypothermia is.

Q3: Did James Cameron ever actually test his “jump and swim” theory?

A3: While he hasn’t jumped off a real sinking liner, he has spent hundreds of hours in submersibles and water tanks. His theory is based on his observations of how the lifeboats were launched and the testimony of survivors who were actually pulled from the water into boats.

Q4: How did Cameron’s deep-sea diving influence his survival theories?

A4: Diving to the wreck 33 times gave him a 3D understanding of the ship’s layout. He knows exactly where the stairs were, where the gates were, and how long it would take to get from a cabin to the boat deck, making his “timeline” for survival much more accurate than a casual observer’s.

Q5: Is it true that the water was actually -2°C?

A5: Yes. Because it was saltwater, the freezing point was lower than that of fresh water. This “supercooled” water causes “cold shock” almost instantly, which is why Cameron emphasizes that his strategy requires “immense courage” and a very short swim.