When comedy was stiff, Lucy danced on tables

In a decade where most sitcoms clung to predictability like a life raft, I Love Lucy emerged as a wild, chaotic cruise ship captained by Lucille Ball herself. It wasn’t just the candy-factory gags or Vitameatavegamin tongue-twisters that left audiences in stitches — it was something rarer: the art of failure turned into performance.

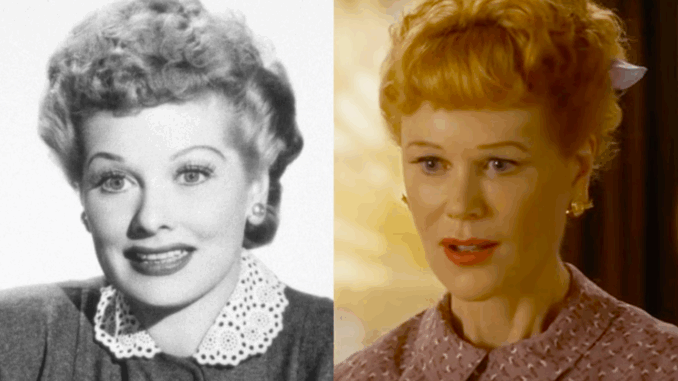

Lucille Ball didn’t simply play Lucy Ricardo. She crafted her. Beneath the goofy exterior and exaggerated facial expressions was a performer who had clocked years in vaudeville, silent film, and B-list movie roles. When CBS finally gave her a sitcom, she didn’t just step into television — she transformed it.

Improvisation in a scripted world

While sitcoms today often lean on improv and writer’s room chaos, the 1950s thrived on strict rehearsal and live-audience discipline. Yet I Love Lucy repeatedly pushed that boundary. Lucille Ball’s physical comedy was so precise, so fluid, that it gave the illusion of spontaneity.

In fact, many of the show’s most iconic moments were born not out of the script, but from Lucille’s personal instinct. The chocolate assembly line? The stomping of grapes in Italy? These weren’t just skits — they were meticulously orchestrated acts of rebellion against tidy, controlled comedy.

A silent feminist manifesto

It’s easy to forget: Lucy Ricardo wasn’t supposed to be the hero. She was a housewife who kept failing. But in her failure, there was freedom. Lucy didn’t ask for permission; she sneaked into Ricky’s shows, disguised herself as a clown, or barged into auditions. She wasn’t allowed to succeed — so she made failure her spotlight.

For 1950s audiences, this was subversive. For modern ones, it’s revolutionary. Lucille Ball didn’t just make us laugh — she gave generations of women permission to be loud, messy, and unapologetically ambitious.