Sanford And Son may have copied other shows, but Redd Foxx was an original (p1)

Remakes have a mixed reputation in popular culture, with the reactions usually dependent upon the medium and the intent. We love an inspired cover song; we mock a dull one. We roll our eyes at the announcement of yet another movie version of an old property, but if the new creative team can make the material feel fresh and relevant, they get a pass for cashing in on a familiar name. And when it comes to television? Well, with TV we don’t tend to talk about “remakes” so much as “reboots,” “reimaginings,” and “rip-offs.” The Office, for example, is based on a British show. But do its 201 episodes really count as a “remake” of The Office U.K.’s 14?

There have been times when television producers edge into true remake territory. Exactly one year after Norman Lear and Bud Yorkin shook up showbiz with their CBS sitcom All In The Family, the partners took their act to NBC, debuting the similar Sanford And Son. Both shows were about cranky old bigots, both were set among the working class, and both were based on British series: Till Death Do Us Part and Steptoe And Son, respectively. But while All In The Family was about the generational divide in a household of white New Yorkers, Sanford And Son hit some of those same notes in a predominately black Los Angeles neighborhood. And there was one other major difference: The NBC series didn’t just borrow its premise from the U.K. For most of its first season, Sanford episodes were direct adaptations of Steptoe.

That’s not unheard of, but it is unusual. In recent years, Americanized versions of British imports like Shameless have started out with episodes that lightly rewrote the shows they were aping; and in the ’70s, Three’s Company (among others) adapted multiple episodes from its source material. But Sanford And Son reinterpreted 16 Steptoe And Son episodes during its first year on the air—so many that it almost became like a Broadway production of a London play. That makes it a useful case study for those who like to think of the proper artistic analogue for television as not movies or novels, but theater.

Could Steptoe And Son’s “The Piano” be thought of as a one-act play? Just the second episode of the series—originally airing on the BBC on June 21, 1962—“The Piano” doesn’t demand any familiarity with the show or its premise to understand either the story or the jokes. It’s a piece of situation comedy where the situation is easy to grasp: A foppish rich man (who never says his name) wants his ex-wife’s piano out of his apartment, so he hires a pair of bickering father-and-son junk dealers to haul it off. While the aristocrat worries that these oafs will harm his priceless antiques, the “rag and bone” men argue among themselves about how hard it’s going to be to move the instrument through the door and down the stairs. They also speculate about whether or not their decidedly fey employer is “kinky.” In the end, the Steptoes determine that the job’s not worth the trouble, so they bail halfway through, with the piano still wedged in the doorway.

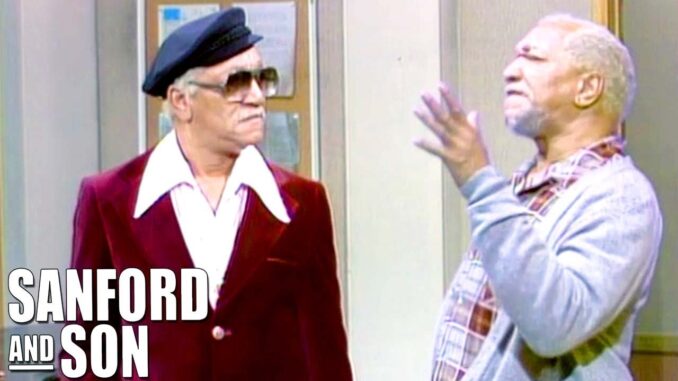

On April 14, 1972—the last week of Sanford And Son’s first season—NBC aired “The Piano Movers,” with a script by Aaron Ruben from a story by Steptoe creators Ray Galton and Alan Simpson. It’s not just the rough outline of “The Piano Movers” that shadows “The Piano.” Ruben also repeats bits of dialogue, and digressive details. Both Harold Steptoe and Lamont Sanford ask their respective rich guy if his wife is dead, and in both cases the man says, “Unfortunately, no.” In both episodes, the employer forces the junkmen to put on elegant slippers so they won’t ruin his expensive rugs; and in both, the grumpy father (Albert Steptoe in one, Fred Sanford in the other) elicits sympathy with lies about his war record, and asks for a drink by saying, “Beer if it’s near, brandy if it’s handy.” And each episode ends with a police officer telling the movers to choose between finishing an obviously impossible task or getting their vehicle out of the street before it’s towed away. As they leave, both the Steptoes and the Sanfords are still wearing the weird-looking soft shoes that were foisted on them.

The biggest change between “The Piano” and “The Piano Movers” is the extent to which Albert and Fred are fascinated by their host’s extravagant wardrobe and surroundings. Albert cocks an eyebrow at the way their employer dresses and at his collection of fancy footwear, and he warns Harold that this stranger could be “dodgy.” But Fred’s way more accusatory, and more curious. “I think he’s a fruitcake, or maybe just a plain fruit,” he tells Lamont. When he peeks at the piano-owner’s checkbook and sees one made out to “Duane,” Fred jokes, “I bet I know who Duane is.” When the man casually mentions that “I have a whole new way of life that I prefer,” Fred says, “That’s what I want to ask you about… ” before Lamont stops him from going any further.