A treasure trove of nearly 350,000 documents, about to be released to the public, reveals new insights about how George III lost the colonies

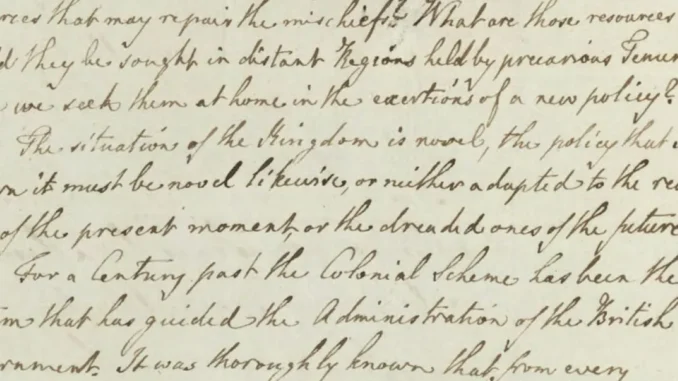

Suddenly after the Revolutionary War, a British father of 15 sat down to think about the world “turned upside down.” He had never seen the American continent, and rarely set foot outside London. But his private papers reveal that he closely tracked the war’s path in maps and regiment lists. A man of routine, he dated his daily letters to the minute as the conflict raged on. He tried hard to picture the England that his children would inherit. “America is lost! Must we fall beneath the blow?” he wrote in a neat, sloping hand. “Or have we resources that may repair the mischiefs?” These were the words of George III—father, farmer, king—as he weighed Britain’s future.

Many Americans, as colonists-turned-citizens, might have been surprised to hear George’s inner thoughts on the war that brought about their new nation. He was, after all, the same ruler that revolutionaries had blisteringly indicted in the Declaration of Independence. There, they called George a “Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant,” one whom they regarded “unfit to be the ruler of a free people.” Over the centuries, popular culture has depicted “America’s last king” in critical fashion. His illness steered the plot of Alan Bennett’s 1991 play, The Madness of George III. More recently, the hit musical Hamilton pictured George III penning a breakup letter to the colonies, titled “You’ll Be Back.”

Now, for the first time in over two centuries, you’ll be able to read the king’s side of the American Revolution and its aftermath from the comfort of your own castle. George III’s essay on the loss of the colonies is part of a private cache totaling more than 350,000 pages, all currently preserved in Windsor Castle’s Royal Archives after a century or so of storage in the cellar of the Duke of Wellington’s London townhouse. In April 2015, Queen Elizabeth II officially opened the trove to scholars, along with plans for the Georgian Papers Program to digitize and interpret documents for a new website, launching in January 2017.

Only a portion of the material, roughly 15 percent, has ever been seen in print. A sea of letters, royal household ledgers and maps abound for researchers to explore. And George III is not alone: Although the bulk of the archive documents his reign, it also contains documents that outline the political and personal views of several British monarchs and their families between 1740 and 1837.

Why open up the once-private royal archive? The Georgian papers are “absolutely key to our shared past,” says Oliver Urquhart Irvine, Royal Librarian and assistant keeper of the Queen’s Archives. “It’s not just about us. It’s important to see George III’s relationship to science, to agriculture, to family and domestic life, to women, to education, and to all kinds of subjects.”

Past scholars have framed the age as one of Enlightenment and revolutionary tumult. But though founding-era figures like John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and others anchor the American side of the saga with their candid correspondence, George III’s views have not always been so tantalizingly within reach. By 2020, the Georgian Papers team will make all material relating to Britain’s Hanoverian monarchs freely available in digital format. “We fully expect this project to lead to discoveries that will transform our understanding of the 18th century,” says Joanna Newman, vice president and vice-principal (International) at King’s College London.

In spirit of collaboration, Windsor archivists have teamed up with the Royal Collection Trust and King’s College London, and reached across the Atlantic for help in bringing royal words to life. The Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture at the College of William & Mary serves as the primary U.S. partner for the project, and has sponsored several research fellows to study the archive. (You can apply here.) In addition, Mount Vernon, the Sons of the American Revolution, and the Library of Congress have all announced their participation.

In 2015, the first wave of the program’s researchers began to explore the manuscripts in earnest. Scholar Rick Atkinson, a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner writes a new military history of the Revolution, recalls that “a bit of magic” clung to his daily commute up to Windsor Castle. He passed through the Henry VIII Gate and the Norman Gate, climbed 102 stone steps, and then ascended another 21 wooden steps in order to reach his desk in the iconic Round Tower. “And there are the papers,” says Atkinson. “George didn’t have a secretary until his eyesight began to fail later in life. He wrote most everything himself.